Online advertising plays a crucial role in the spread of misinformation. As Bill Fitzgerald wrote last week,

Right now, the status quo in adtech is to sell to all sides, and profit from both the arms race and the battles. While our discourse and news ecosystem remains mired in misinformation, adtech pulls profit.Adtech profits when we read lies, and adtech allows liars to earn revenue.Adtech profits when we read hate speech, and adtech allows the people who spread hate to earn revenue.Adtech profits when places like the Huffington Post convince writers to publish for “exposure,” and adtech allows the Huffington Post to generate revenue for these exploitive practices.Adtech profits when people read traditional news outlets, and adtech allows these news outlets to generate revenue.

In my follow-up post on adtech and misinformation, I concluded

The more Bill and I study extremist communities online, the more convinced we are that standard advertising practices play a significant role in the spread of misinformation. Further, while many are rightly encouraging us to think critically about the information we consume and the sources we trust, it’s also becoming clear to us that mainstream news media is playing the same advertising game, and by the same rules, as the spammers and the spreaders of misinformation. And as long as the pay-per-click advertising model rules the roost, and news sites (mainstream and extremist) continue to be the largest users of data-collecting adtech, online, data-driven propaganda will be a real possibility, not to mention a lucrative business opportunity.

We both shared a lot of data and examples of what we’ve been finding as we research the spread of misinformation and extremism online. But what does this misinformation network look like?

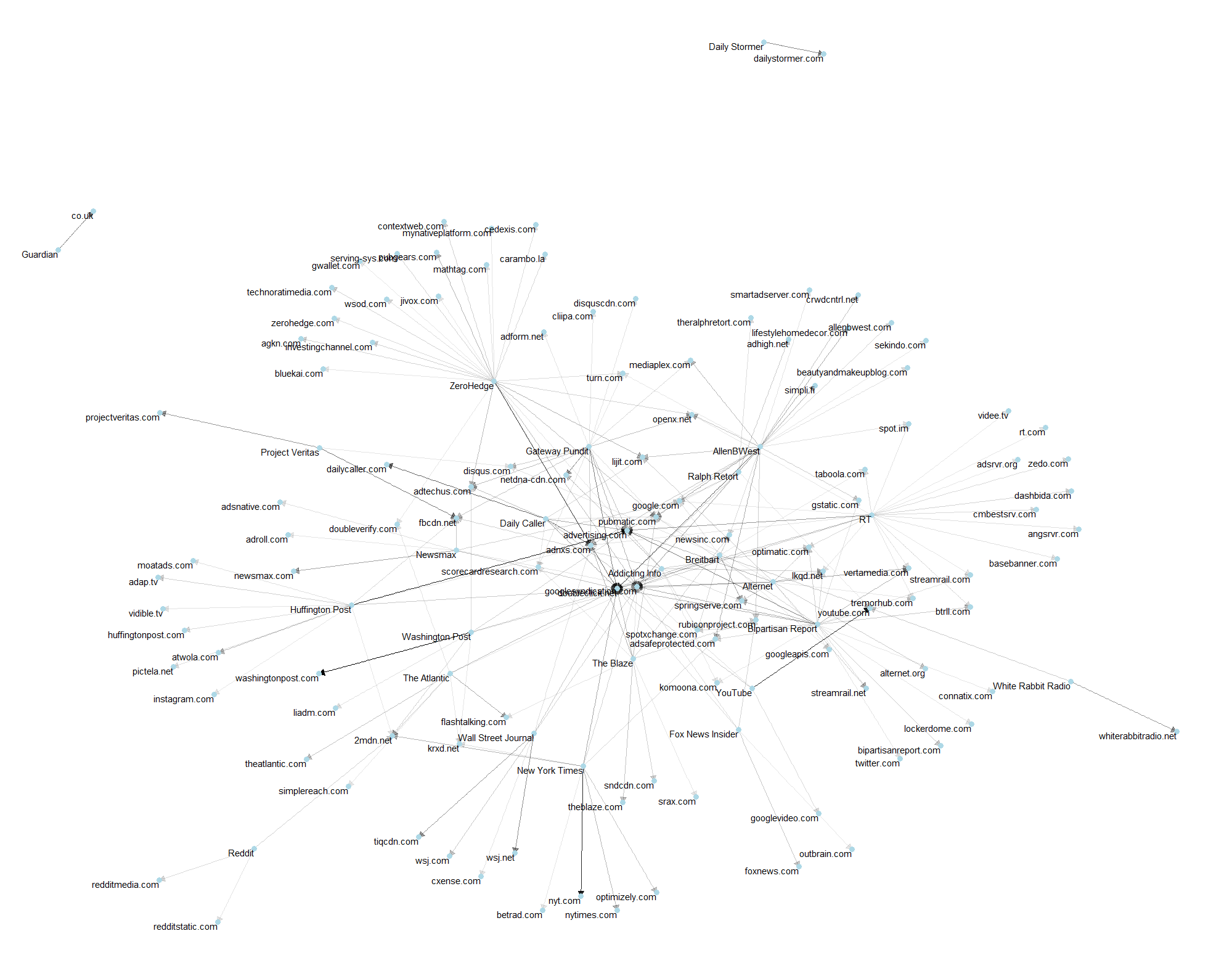

Here’s what it looks like…

This network graph (click the image to enlarge) takes the data from Bill’s analysis and arranges it spatially. Each node (dot) in this network represents a domain on the web. The arrows tell you what happens to your data when you visit one of those domains. Darker arrows signify more data requests. (For the sake of clarity, we only included connections made at least ten times in the course of visiting three pages on a site.)

For example, when you visit the New York Times, it sends requests for data from its own network of servers, as well as Google (both Google Syndication and Doubleclick.net), 2mdn.net, and a variety of other ad servers. When you visit a page on RT, it makes requests from even more sites. And while most of these requests are requests for data, most of them also involve sending data. Data about your location, your browser, your window size, the network you’re accessing their website from, the page that you’re on, what you clicked on, if you’re logged into Google or Facebook, if you have a cookie from one of their partners installed, etc. This is all in the service of providing you a more “personalized” experience (without, or so they claim, using your truly “personal” data). It’s also in the service of providing themselves revenue in the form of advertising, and in some cases, data collection with the purpose of trading or selling that data.

This network graph also shows something beyond simply where your data goes ― which, I’ll admit, was frightening the first time I saw it. It shows how your data can travel between entities, if any of those entities are so inclined to share, trade, or sell it. That realization ― that an entity I did not explicitly decide to send my data to would both receive my data and be in the position to share it with others ― frightened me. Still frightens me. It’s the reason I have ad blockers, HTTPS Everywhere, Privacy Badger, DuckDuckGo, Tor, and other privacy tools. Because, as Bill wrote and this graph shows, ad brokers work indiscriminately with all kinds of content providers. And it doesn’t take much for data collected while I browsed my favorite news source to make it into the hands of Breitbart (associated with, though no longer managed by, White House Chief of Staff, Steve Bannon) or RT (formerly Russia Today, but still funded by Putin’s government).

Something else this graph hints at is the similar associations that different sites have with adtech vendors. The algorithm that places nodes in the graph promotes clarity by putting nodes with similar associations near each other, and thus nodes with more connections near the center. This is why the most-connected nodes (many of which are owned by Google) are in the center, and why many of the far-right sources are clumped together, as are the mainstream news networks. But that representation is imperfect, being somewhat incidental. So I made a second visualization that shows which websites have the most adtech connections in common.

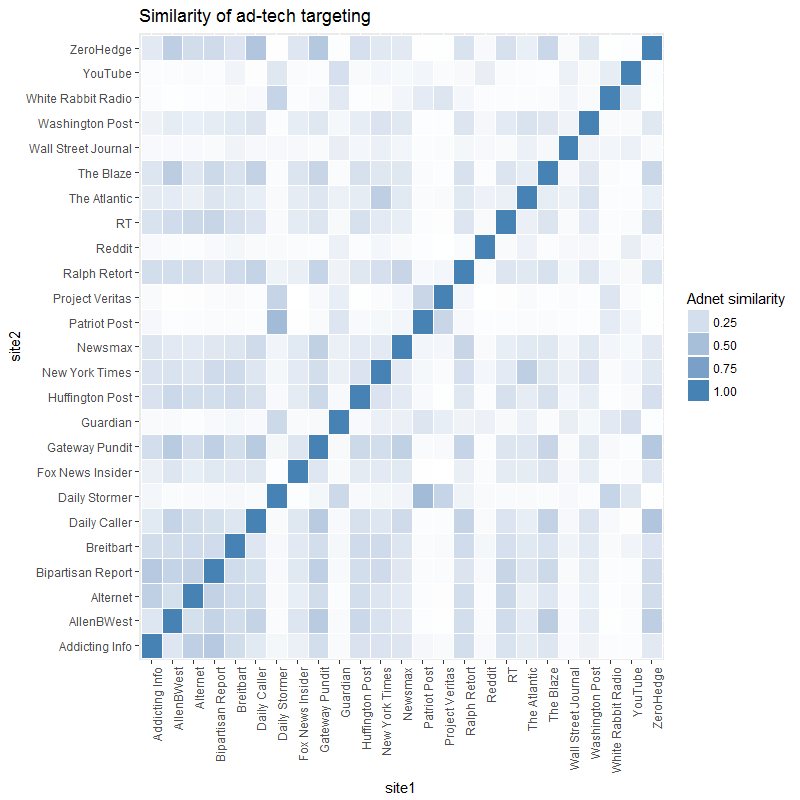

For this visualization, I took the list of background requests made by each site, and compared them all to each other for similarity. For example, when visiting three pages on Breitbart, Bill’s analysis found Breitbart making 87 background requests. RT, on the other hand, made 121. 51 of the requests made by each of those sites went to the same domains. That’s 59% of Breitbart’s requests going to servers called by RT, and 42% of RT’s requests going to servers called by Breitbart. To come up with a single number, I simply multiplied the two values together (0.59 * 0.42) to get a share product of roughly 0.247. (The product method ensures both simplicity and that very small numbers don’t exert undue influence on the result.) I calculated a share product for every pair of sites in Bill’s dataset, and produced the heat-map above, with darker blue squares representing higher degrees of overlap in the background requests made by these sites.

Some of the results aren’t particularly surprising. I would expect conservative sites like Patriot Post and Daily Stormer to have a strong degree of similarity. I’m also not surprised by the fact that a mainstream news source like The Atlantic has its most significant overlap with the New York Times and the Washington Post.

But look at The Guardian. It most strongly overlaps with Daily Stormer and YouTube, which is turning out in our research to lean very far right as an information source on social media. Perhaps more alarming, though, look at the rows represented by mainstream sites like the New York Times, The Atlantic, or the Washington Post. There’s a lot of blue in each of those rows! That’s because mainstream news media are among the most prevalent users of adtech. And thus, they are more likely to overlap significantly with the adtech choices of more fringe sites.

Now mainstream media have significant motivation to safeguard the data of their readers, both to keep them as customers and to maintain their credibility as a source of good information. But what about the adtech they use? Would you feel particularly violated if adnxs.com or 2mdn.net were in the news tomorrow as the source of a major data breach? And yet, outside of Google, those are two of the most prevalent sources of adtech in the sites we examined. The integrity of these ad sources are crucial to our ability to own, control, and safeguard our personal information. If any one of them fails, we could be in a heap of trouble. And yet just stopping by the Washington Post to read one or two articles could potentially expose information about us to dozens of different companies, most of which we know nothing about, and most of which do business with sites run by extremists or ― in the case of RT ― a hostile foreign government.

Like I said in my last post, this has to change. But first, we need to grok it. It can be hard thing to get our heads around, and a scary thing to ponder. But especially as the US government increases its surveillance activities and makes corporate surveillance easier to do without our knowledge, it’s more important than ever that we get our heads around this, so we can resist.

Good night. And good luck.

Header image by Peng Liu.