The more we study extremist communities online, the more convinced we are that standard advertising practices play a significant role in the spread of misinformation. Further, while many are rightly encouraging us to think critically about the information we consume and the sources we trust, it’s also becoming clear to us that mainstream news media is playing the same advertising game, and by the same rules, as the spammers and the spreaders of misinformation. And as long as the pay-per-click advertising model rules the roost, and news sites (mainstream and extremist) continue to be the largest users of data-collecting adtech, online, data-driven propaganda will be a real possibility, not to mention a lucrative business opportunity.

This is the third post in a series on misinformation, propaganda, and digital media by Bill Fitzgerald and myself. We are currently researching the places that political extremists get their (mis)information, and the role that adtech and social media play in the spread of that misinformation. To learn more, see our earlier posts: Mining Twitter data with R, TidyText, and TAGS and Adtech and Misinformation: the Middlemen Who Sell to All Sides.

Where do people get their “news”? Do Americans on the political right get their information from different sources than their left-leaning counterparts? And what about so-called “fake news”? How prevalent is it? And is it a problem for everyone, or more of a problem for a certain political group?

These are the questions underlying the research that Bill Fitzgerald and I have been conducting these past few weeks. It started with a simple question from Bill on Twitter: how difficult would it be to assemble a list of domains commonly tweeted by far-right accounts? My answer was not very. And then I began collecting tweets.

To be specific, I collected 591,680 tweets from early March. I used the TAGS Twitter archive tool to collect tweets indiscriminately from four right-wing hashtags ― #maga, #americafirst, #pizzagate, and #whitegenocide ― and four left-wing hashtags ― #resist, #trumprussia, #impeachtrump, and #blacklivesmatter. (I tried to mix hashtags that would get both mainstream and extreme perspectives from both sides.) The resulting dataset had 258,173 tweets from right-wing hashtags and 333,507 tweets from left-wing hashtags, collected beginning on March 3, 2017, and ending when each respective TAGS archive reached the data limit for its Google spreadsheet (in some cases three days, in others almost two weeks). It’s an imperfect dataset, to be sure. But it’s a good place to start.

What did we find?

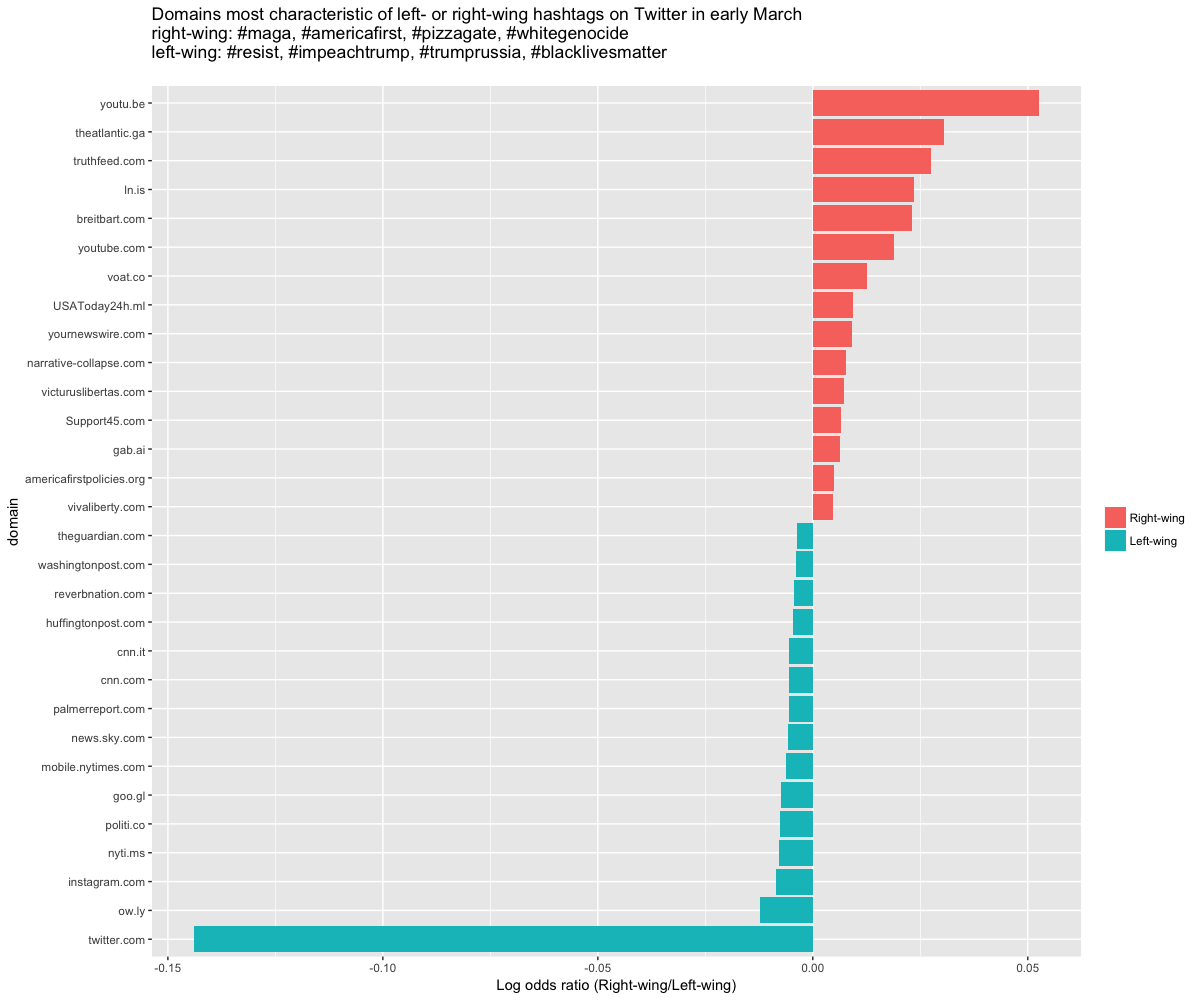

Let’s start with the money graph: the websites that most uniquely define right-wing and left-wing information sources in this Twitter archive. To determine this, I calculated an odds ratio, a statistical measurement that tells us if a website is more likely to pop up in right-wing tweets, left-wing tweets, or equally likely to pop up in either. This graphic shows the domains with the largest left-leaning and right-leaning odds ratios (on a logarithmic scale to make the visualization easier to read). Click the image to enlarge.

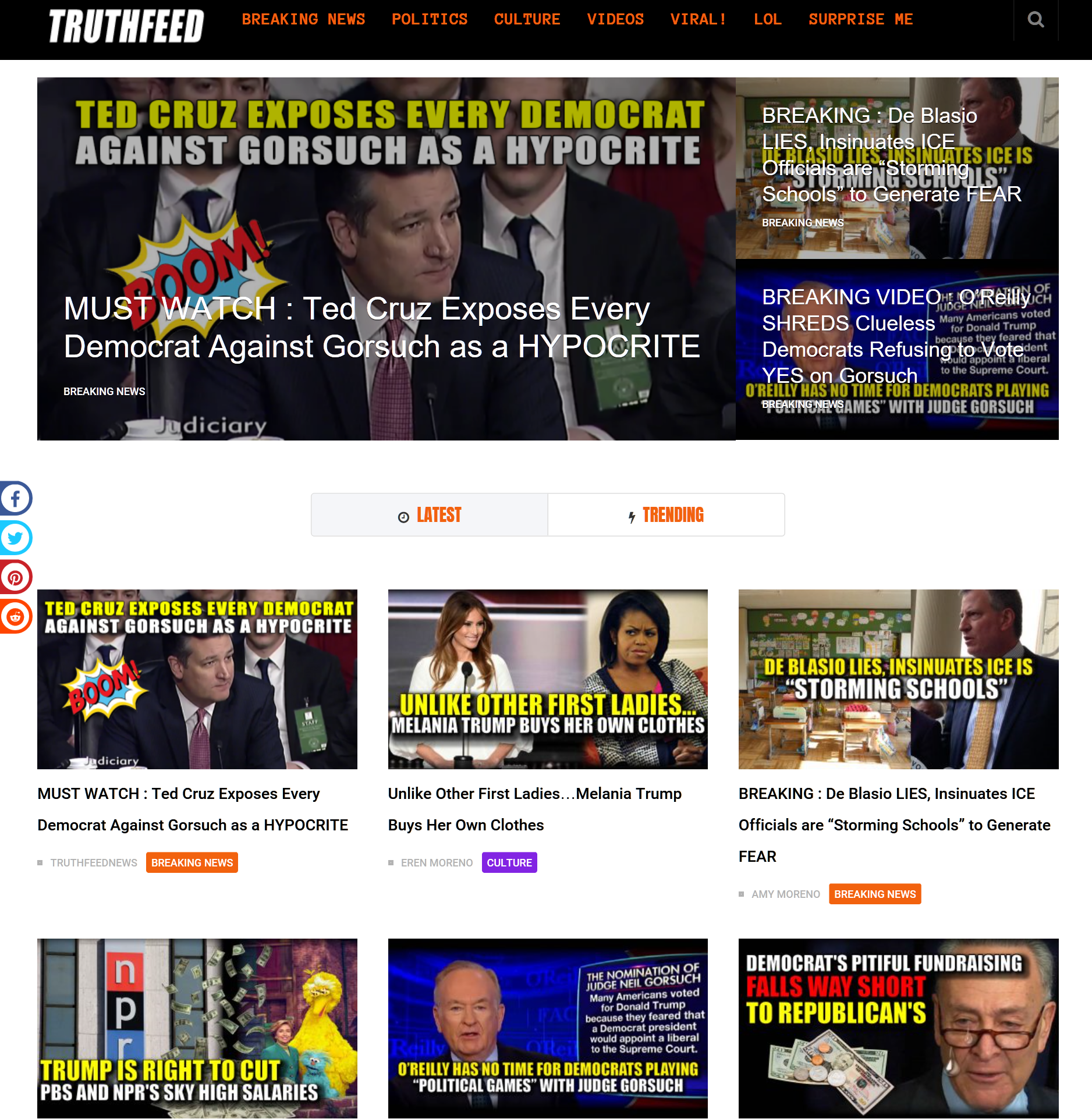

On this graphic, we can see that left-wing tweets are biased in favor of Twitter, Instagram, and mainstream news sources. Though there are some left-leaning partisan sites on the list, the list is dominated by mainstream sources like the New York Times, Politico, Sky News, CNN, Washington Post, and The Guardian. On the right, however, there are no mainstream news sources. Aside from YouTube (mostly independent “news” sources), most links come from far-right sites like Breitbart, fake-news sites like TruthFeed, and ad-tech/malware sites like theatlantic.ga and USAToday24h.ml.

There are several important takeaways from this graphic. First mainstream news media tend to appear more commonly in left-wing hashtags. Second, though there are left-wing fake news sites further down the list, the most characteristic right-wing sites include a large number of fake news sites. However, I don’t think this means that right-wing Twitter users are more likely to be sharers of misinformation per se. There’s something else going on here. Specifically, the presence of malware sites suggests a significant bot presence, particularly in right-wing hashtags.

This is worth unpacking more.

One of the top fake/malware sites in this tweet corpus is theatlantic.ga. The domain appeared 2651 times in the corpus, more than TruthFeed (2384 times), Breitbart (2036 times), or the New York Times (1816 times). Only Twitter (89,218 times), YouTube (12,268 times), and a couple link shorteners appear more often. What is theatlantic.ga? If you visit the domain directly, it redirects you to adf.ly, a site whose motto is “Get paid to share your links on the Internet!” (Aside: there’s a reason I’m not linking directly to these domains.) adf.ly (whose logo is a bee?!) offers services that help people sell advertising on their sites, “Pay for real visitors on your website,” and track aspects of the identity and behavior of those visitors. They also offer an API (application programming interface) that makes it easy to automate the process of generating and sharing links. The way it seems to work is similar to other link shorteners (like bit.ly), but instead of just making a long URL short and tracking clicks, it embeds ads along the way. Users who click on an adf.ly link see a brief ad on their way to the page they intended to go to, without embedding any ads on the actual page.

Businesses like adf.ly mean that

1) it’s easy to advertise on your site with minimal technical knowledge,

2) it’s easy to advertise on other people’s sites by sharing links to them via social media, and thus

3) it’s possible to make money off of ads on other people’s sites without even having your own website.

All you need is a Twitter account (or bot, or army of bots), and if you have an audience for those Twitter bots, you have people who will click on the links you provide, which will in turn generate “advertising” revenue for you, the bot owner. (Not the site owner.)

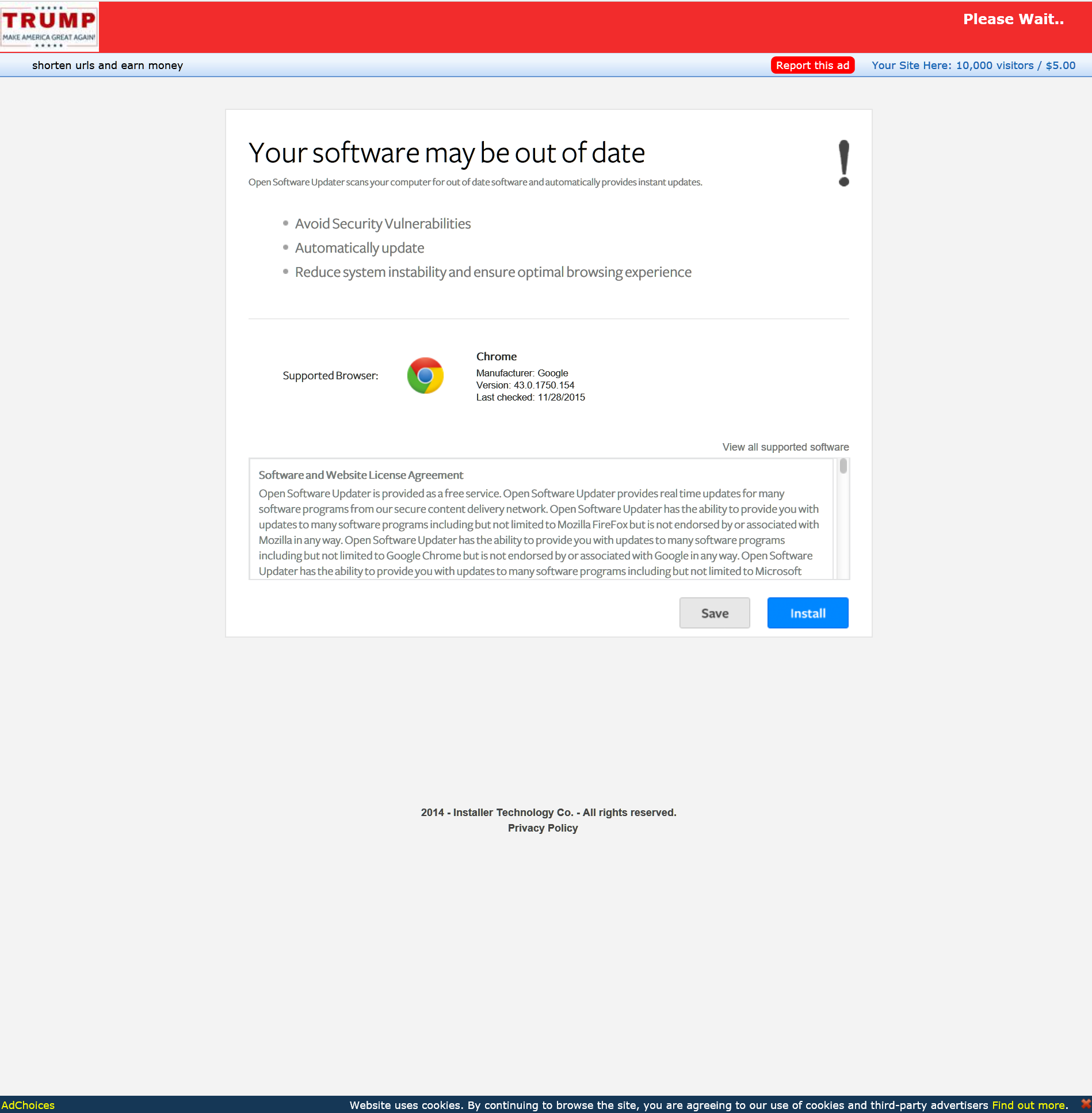

So what kind of pages are adf.ly sites like theatlantic.ga sending Twitter users to? The most frequently shared theatlantic.ga link is theatlantic.ga/7At (13 times). (DO NOT VISIT THAT LINK. IF YOU DO, BE SURE NOT TO CLICK ON ANYTHING!) Here’s what that page looks like.

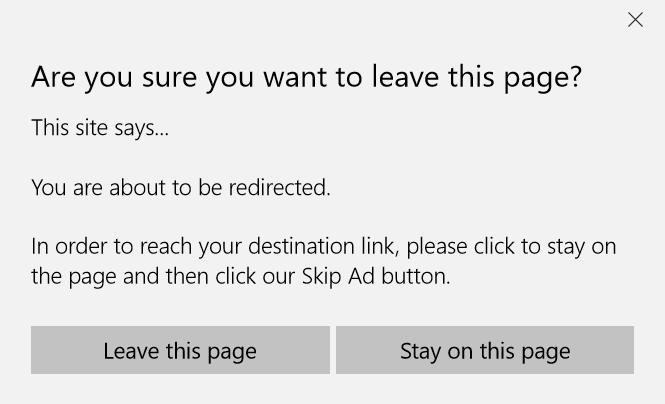

It’s a page that makes only a minimal attempt to be right-wing (the Trump campaign logo in the upper left), but instead masquerades as a browser security warning in order to get users to download malware. (I’m assuming it’s malware. I didn’t actually click on it!) When you try to close the page, you get a popup message discouraging you from leaving the page.

We’ve seen all this before. But in this Twitter dataset, we see it a lot, and we see it more on right-wing hashtags than on left-wing hashtags.

So what! People are spamming hashtags. We’ve seen that before, too. We can just ignore it. And it’s probably not going to have an effect on people, right? I mean, this isn’t misinformation, it’s just spam. … Right?

Not quite.

Let’s look at some of the Twitter users who share these links. Here are the ten most prolific accounts tweeting links to theatlantic.ga.

| user | number of tweets |

|---|---|

| Imwithtrump4 | 282 |

| Hopetotrump | 247 |

| AllWithTrump5 | 241 |

| FollowersofTru2 | 230 |

| americaxtrump | 179 |

| ALWAYSTRUE19 | 137 |

| Changewithtrump | 104 |

| Tru_republicans | 103 |

| Republicanfore2 | 88 |

| FloridaxTrump | 54 |

I visited the first account, and lo and behold, it had been suspended! (Remember, those 282 tweets containing theatlantic.ga are only a couple weeks old.) The second account, Hopetotrump, in many ways looks like a typical right-wing Twitter user. Patriotic banner image, content consistent with right-wing ideas and ideals, and what looks like links to many right-wing and mainstream news media. But on closer inspection, we see that the links they are tweeting are all theatlantic.ga/something. And that /something tends to be in sequential order. (Right now, the latest links are /Bz9, /Bz6, /Byq, /Byp, etc.) Each tweet contains a headline, an image, and a conservative hashtag. The hashtag puts the tweet in front of people who otherwise would not follow the account (this account as only 188 followers, but some of these accounts have tens of thousands), and the headline/image combination are designed to entice right-wing readers to click.

This account tweets very often (and doesn’t take a break to sleep), so someone must be working hard to generate all that content, right? Take one of their tweets from this morning:

I searched twitter for this text and found this:

In fact, these feeds have a lot of tweets in common. It seems that accounts like Hopetotrump are simply mining conservative Twitter accounts for text and images, and substituting their own malware links and random conservative hashtags, with the goal of grabbing the attention of conservative readers and getting them to click on a link that will make them money. In fact, when you look in more detail at the data coming from this dataset, you can see that many of these malware sites own multiple bots that tweet exactly the same content.

So the recipe seems to be this:

1) Mine existing conservative Twitter accounts for content.

2) Substitute a malware link for the original link, and append a commonly read conservative hashtag.

3) Tweet that new content out via multiple Twitter bots.

4) Collect data and money from adf.ly and/or malware.

The content is generated by others, there are minimal webhosting costs involved, and even the “click-bait” properties of the “ads” are engineered by others. Scripts abound on the internet for mining Twitter content and remixing it to make your own content. (I even have my students do this, albeit in more artful, ethical ways.) So this is a pretty simple way to make at least a few bucks on the internet without much technical knowledge.

But this still seems like classic spamming and phishing. What does this have to do with misinformation?

Both Mike Caulfield and I have written about the effects of casual scrolling on social media. When we see the same claim repeated often enough, especially when our guard is down, we slowly become more predisposed to believe it. Further, social media platforms go to significant lengths to ensure that content looks uniform, meaning that it doesn’t matter how ugly TruthFeed.com looks. We see their tweets alongside, and with a similar look and feel to, tweets from legitimate sources. We also know that the more polarizing claims tend to get the most clicks, and thus make the best advertising fodder.

The sum of all this is that the most polarizing claims are the most repeated by the bots, and as readers see them in aggregate over time, they become more plausible in our unconscious mind. We may not click on the links, we may not even engage or believe the idea when the bot shares it. But once one of our friends, relatives, or colleagues shares that same claim ― perhaps from the original site the spammers stole content from ― we will be that much more likely to believe the claim. That gives the more polarizing, partisan sites more psychological power, and that lays the foundation for more purposeful ― and successful ― propaganda campaigns.

The more Bill and I study extremist communities online, the more convinced we are that standard advertising practices play a significant role in the spread of misinformation. Further, while many are rightly encouraging us to think critically about the information we consume and the sources we trust, it’s also becoming clear to us that mainstream news media is playing the same advertising game, and by the same rules, as the spammers and the spreaders of misinformation. And as long as the pay-per-click advertising model rules the roost, and news sites (mainstream and extremist) continue to be the largest users of data-collecting adtech, online, data-driven propaganda will be a real possibility, not to mention a lucrative business opportunity.

And that has to change.

More on that in future posts…

Header image by =Pixabay (CC0).