Can artificial intelligence identify potential terrorist activity?

This past week, BBC News published an article, “Facebook algorithms ‘will identify terrorists’”. It describes the content of a 5,500-word letter posted by Facebook head, Mark Zuckerberg, about the future of the company, including the role that machine-learning algorithms will play in filtering and classifying content. The headline, like much journalism surrounding machine learning and artificial intelligence, is overblown and sensationalized. In fact, the quote in the headline isn’t even a quote! Zuckerberg never says “will identify terrorists” in the letter described in the article.

However, Zuckerberg does indicate that Facebook is

starting to explore ways to use AI to tell the difference between news stories about terrorism and actual terrorist propaganda so we can quickly remove anyone trying to use our services to recruit for a terrorist organization.

To those worried about the role of artificial intelligence in society, using social media data to identify people who may perpetrate an attack in the future is a frightening proposition. Now, Zuckerberg writes that a system to distinguish news about terrorism from actual terrorist propaganda is “technically difficult” and “will take many years to fully develop”. But researchers at Columbia university are already working on tools to monitor Twitter activity from known gang members and cross-reference that activity with criminal activity committed by gang members. The hope is that they will uncover patterns in the relationship of social-media data to known crimes that will help them predict, and prevent, future crimes. So it makes sense that law enforcement officials would want to extend this possibility to Facebook, as well as to major terror attacks.

But is it even possible? And if it is, what ethical limits would we need to put into place?

How machines learn

When Zuckerberg talks about using algorithms to parse terrorist propaganda from news about terrorism, he’s talking about a classification algorithm. A classification algorithm is an example of a supervised machine-learning algorithm, meaning that the potential outcomes are known beforehand. Think of Google Books. When Google takes a scan of a book page, its optical character recognition algorithm looks for elements in the image that match closely with one or more known possible characters (all the letters A–Z, upper- and lower-case, with various diacriticals, along with numerals, symbols, etc., all in a variety of font types). Facebook’s face recognition is similar. It scans an image for objects that fit the known category of human face, and then compare those objects to a set of known faces (likely starting with the friends list of the person who uploaded the image).

In each of these cases, the output categories are known: letters, numbers, and symbols; faces of a set of individuals; etc. And while the specific algorithm used to classify elements as belonging to one of those categories may vary, the general process is the same:

- Take a large set of examples where the outcome is already known (such as 1000 images of upper-case A's, 1000 images of upper-case B's, etc.).

- Divide the set of examples into *training* data and *test* data (often a 70/30 split).

- "Train" the algorithm on the training data. Or in statistical terms, fit a model that corresponds to the data.

- Test the accuracy of the model by running the test data through it and comparing the algorithm's classification results to the already known answers.

- Refine the model and/or augment the dataset to attempt to improve the results (taking care to avoid p-hacking).

- Lather, rinse, repeat.

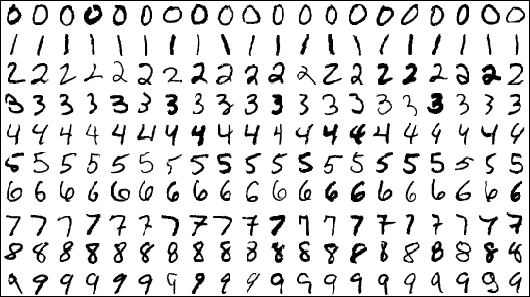

Example handwritten digits from the MNIST dataset.

To build a successful classification algorithm, you need a lot of data. For example, the famous MNIST dataset of handwritten digits contains 70,000 images of handwritten digits (0–9). That’s 70,000 images (60,000 to train, 10,000 to test) of just ten potential output categories! (And let’s say you develop an algorithm that performs at a very high 99% accuracy level. That still means that you misclassified 100 images!)

Let’s apply this to gang crime. In a simplified version of the algorithm, the output would be crime committed (true/false), and the input would be the amount and kind of social media activity from known members of a gang. The input dataset would come from mining the social media activity of known gang members, and it would be cross-referenced with police reports, charges filed, and/or convictions won against gang members. Split the data into training and testing data, train the algorithm to recognize patterns in social media activity that strongly associates with the presence/absence of criminal activity, test those patterns on the remaining data, and determine the accuracy of the crime-predicting algorithm.

Predicting crime from tweets is far more complex than recognizing handwritten digits! But there’s also a lot of data that comes with those tweets: text content, user ID, other tagged individuals, timestamps, language, device used (mobile vs. desktop), and sometimes the user’s location. And while there may not be 70,000 examples of crimes committed by an individual, or even a single gang, the number of crimes committed by gangs in a large city each year does number in the thousands, and they come in clear, legally delineated categories like homicide, robbery, burglary, assault, etc. So while predicting crime from tweets is not without its technical and ethical challenges, it is conceivably possible, and law enforcement has already begun to attempt it.

Predicting terrorism

Terrorism is different. Despite the broad surveillance activity uncovered by whistleblowers like Ed Snowden, the potential dataset for predicting terror activity from things like social media activity is much smaller. Between 2001 and 2011, there were 207 terror attacks in the United States, far fewer than the number of gang-related crimes in one year in a large city like Los Angeles or Chicago. And there are many more known gang members than known terrorists in the US, making gang social-media activity much easier to monitor and analyze than terrorist activity.

There’s a common maxim in data science: a simple algorithm with a lot of data beats a complex algorithm with less data. Or put another way, big data beats sophisticated algorithms. But what happens when you don’t have enough data? You have to rely on a more sophisticated algorithm. That means you need experts to provide information and insights that can fill in the gap of what the data would tell you on its own. In academic terms, you need theory to stand in for lack of empirical observation. This increases the risk of human error like bias and conclusions drawn from incomplete information, which accompanies the already elevated risk of statistical error (variance due to random chance).

This increased potential for error means a higher likelihood of incorrect predictions: terror attacks not predicted and erroneous accusations directed at law-abiding individuals. Without a major breakthrough in the math, the technical solution to this problem is to gather more data. Translation: wait for more terrorist attacks. That’s untenable.

Parsing the difference between propaganda and news is a whole other beast. Mathematically speaking, this is doable. There are copious examples of both, and there are many experts in the world who could advise Facebook (or others working on it) on features for the algorithm to hone in on. It’s clear from recent events that Facebook’s engineers aren’t there yet. But this is conceivably possible.

The case of Napalm Girl

Facebook already uses filters to detect objectionable content, though. And it clearly doesn’t work as desired. Recently, Facebook censored the famous, Pulitzer-Prize-winning photograph, “Napalm Girl”. In response to complaints, Facebook told ArsTechnica:

While we recognise that this photo is iconic, it’s difficult to create a distinction between allowing a photograph of a nude child in one instance and not others.

At the time, Facebook treated this as a policy issue. But it’s really a scale issue, and therefore a machine learning issue.

The problem is that for most people, there are contexts in which an image of a nude child is acceptable and those in which it is not. And legally, there are contexts in which it is felonious and contexts in which it is not. The amount of potentially objectionable images posted to Facebook is mammoth. To detect and filter objectionable images from the platform, Facebook must either hire a large number of people to view images and approve/block them (and quickly!), they must train a machine to do it automatically, or they must train a machine to do some automatically and flag others for human review. They currently do some of each, and according to Zuckerberg’s recent letter, they want to automate more of the process.

Let’s think about this from a machine-learning perspective. If you want to train a machine to classify an image of a child as acceptable or unacceptable, the mathematically preferred way would be to assemble a large collection of both objectionable and innocuous images and use them as you train, test, and refine your algorithm. But collecting and using a large set of images of children, some of which are pornographic, would both be both illegal and reprehensible.

Instead, you could use a more complex system. For example, combining a well trained classifier for children’s faces with one that detects the presence/absence of clothing in an image. Such a combination could, conceivably, detect child nudity. But how can you use an algorithm to parse the nuanced boundaries between editorial journalism like “Napalm Girl” and child pornography? To my understanding, given the current state of machine learning, you can’t.

Machine learning as stereotyping

There’s another ethical issue regarding Facebook’s use of machine learning to filter content for terrorism or other criminal activity. Machine-learning classifiers are meant to discover general trends. They are statistical approaches, not individualistic.

When Netflix and Pandora serve up movie and music recommendations, they don’t do so by getting to know you, but by using the watching/listening histories and ratings of millions of customers to identify a number of clusters of people with similar tastes. They identify the cluster(s) to which you belong, and then recommend that you watch or listen to things you’ve haven’t seen or heard before that are liked by others in your cluster. While it may be more “personalized” to receive music and movie recommendations based on that clustering, rather than more general averages, you are still being treated as a member of a class ― a stereotype ― not as an individual.

When predicting what song someone might want to hear next, this is no big deal. But when predicting crime or terrorism, it’s a huge problem. If Pandora serves up a song I don’t like, I tap the thumbs-down icon, the model learns, and Pandora gives me a new song. (And usually they follow a thumbs-down with a song I’ve already given a thumbs-up, so I’m less likely to close the app in frustration after three or four bad songs in a row.) But when the FBI predicts I’m about to commit mass murder, and therefore they increase surveillance on me, intercept my mail, tap my phone, monitor my electronic communications, visit my employer … it’s a violation of my constitutional rights and a waste of law enforcement resources, not to mention a stain on my reputation if word gets out.

“Artificial intelligence” or applied statistics?

Machine learning can do some really cool things! That’s why I like it. But it’s not really “artificial intelligence”, as many journalists ― and even Mark Zuckerberg ― characterize it. Machine learning is simply statistics, conducted computationally, and often applied at unprecedented scales. Like all statistics, there will always be error, and at large scales, that error, left unchecked, brings potential for enormous human and environmental consequences.

So by all means, Facebook, improve your filters and your classifiers. But we must constantly be examining the ethical implications and the unintended consequences of our technological work, especially as we use technology at large scales in new domains like this. Let’s hope that’s part of the “technically difficult” work they’ll be doing over the next few years.

Featured image by Nicolas Nova.