How many tenure-track professorships are available each year in music theory? How many music theory PhDs graduate and go on the market each year? How many people apply for the typical music theory faculty position?

These questions are essential for graduate students, and those considering graduate school, to explore. A PhD is a major life investment, even if it is funded, and it’s important to have the facts at the outset. But this information is difficult to find, and it is often difficult to compare institutions’ claims about job placement when they are available, as institutions sometimes “count” things differently. (For example, does that 100% job placement include those who left the profession? And did they do so because of bleak job prospects? Perhaps even after a couple years on the market?) Job postings often don’t help much, either, as they don’t hang around long enough to do multi-year studies.

But we can get a little bit of an idea of what the job market for music theorists looks like, thanks to some crowdsourcing work on the Music Theory/Composition Job Wiki. This data is certainly not complete, but it’s the best single source for job postings in music theory, and many of those postings are accompanied on the wiki by the name of the person who won the position, their PhD-granting institution, the year they finished the PhD, and where they are currently employed. As with any real-life data set, there are missing entries, and missing data for some of the entries included. However, it’s a start. And hopefully, as humanities jobs in higher ed become scarcer and more precarious in general, the Society for Music Theory (or some other research group) can collect information that paints a more complete picture.

But for now, here are some trends we can see on the wiki…

How many (tenure-track) jobs are there?

For jobs beginning in the academic years 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17, there are a total of 116 theory only jobs in the US and Canada on the wiki. (To keep things clean, I’m leaving off theory/composition, theory/musicology, and theory/applied positions. While there are a large number of those, a given individual will only qualify for a small subset of them, and will also have additional competition from non-theorists.) That’s roughly 39 theory jobs per year.

But you’re after a tenure-track position, you say? The good news is that most of those jobs are tenure-track. There are 78 tenure-track jobs in theory only listed on the wiki (two-thirds of the total jobs). However, that only comes to 26 tenure-track jobs in music theory per year.

T W E N T Y - S I X

It wouldn’t be difficult for the 5–7 largest graduate programs in North America to produce that many PhDs each year. But, of course, there are more than 5–7 programs. And there are people who graduated in the past few years still looking for a job. And people with a job looking for a new one…

Who gets the jobs?

Where did those lucky 26 people get their PhDs? What were there research areas? Are some demographics favored over others on the market? Again, there’s not a lot of data assembled. But we can find some interesting starting points on the wiki, looking at PhD-granting institutions.

Of the 116 theory-only jobs on the wiki from the past three years, only 66 list the job winner and their PhD-granting institution. That may or may not be a representative sample — there may be certain types of jobs and/or graduate schools where students/candidates are less likely to report their new job on the wiki or be reported by a colleague. That caveat in place, here are the numbers.

Here is the PhD-granting institution breakdown for candidates winning jobs (tenure-track and non-tenure-track together):

| PhD-granting institution | jobs won by graduates in 2014–16 |

|---|---|

| Eastman | 9 |

| Florida State University | 8 |

| CUNY | 7 |

| Yale University | 7 |

| Indiana University (incl. 1 DMA) | 5 |

| UT–Austin | 4 |

| Northwestern University | 3 |

| University of Michigan | 2 |

| University of Minnesota | 2 |

| University of Washington | 2 |

| institutions with one job won | 17 |

| jobs won with no PhD institution listed on the wiki | 50 |

And for tenure-track assistant professor (or equivalent) only:

| PhD-granting institution | jobs won by graduates in 2014–16 |

|---|---|

| CUNY | 6 |

| Eastman | 6 |

| Florida State University | 5 |

| Yale University | 5 |

| Indiana University | 4 |

| UT–Austin | 4 |

| Northwestern University | 2 |

| University of Michigan | 2 |

| University of Minnesota | 2 |

| institutions with one job won | 11 |

| jobs won with no PhD institution listed on the wiki | 31 |

There are 47 tenure-track jobs for which the wiki lists the winner’s PhD-granting institution. Notice that 55% come from the top five institutions. In fact, 25% of them come from just two schools in a single US state — CUNY and Eastman.

It’s worth noting that in the case of Eastman, FSU, and Indiana, these are big programs — lots of faculty, lots of students. It makes sense that they would be high on the list. However, Yale and especially CUNY are fairly small programs, with 2–3 students graduating with music theory PhDs most years. I don’t have data on graduation/matriculation ratios, time to degree, or job placement from these institutions, so don’t take an institution’s being high on this list as a recommendation from me for graduate study — nor the opposite. There are a lot more factors (and some missing data points) to consider when making a decision about whether, where, and when to attend graduate school.

How quickly do music theorists get jobs?

This is a pressing question often overlooked in these discussions. I had a family when I graduated — a wife (who worked), two young kids, and a condo to sell. Especially when working outside of academia between the PhD and the job application can be a point against you in some eyes, going straight from grad school to at least a decent “starter” job is a high priority for many. And if you already have a family that you don’t want to move across the country three times in as many years, a stable job at graduation is incredibly important.

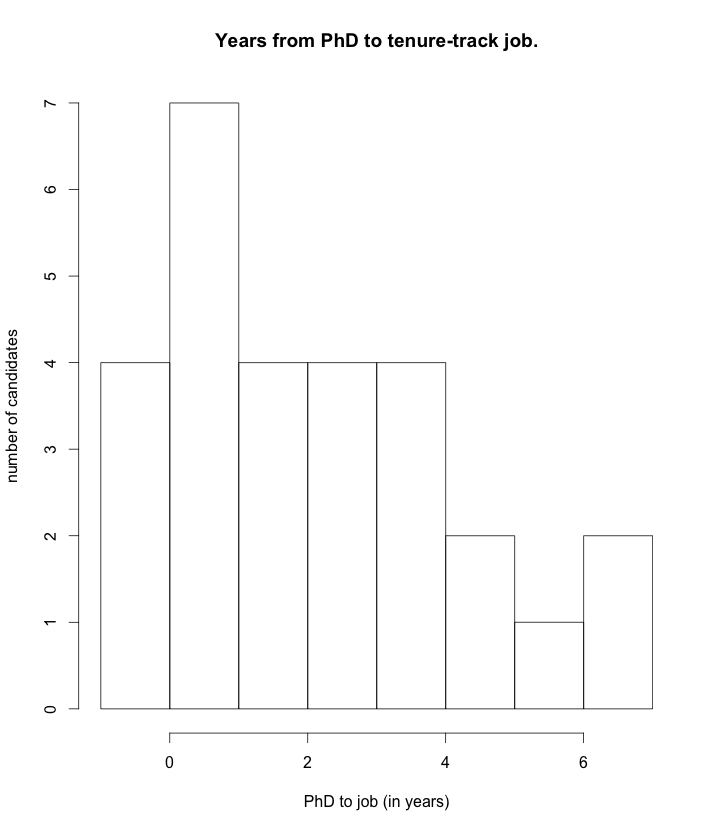

For all the jobs on the wiki where PhD date is listed (plus a few that I knew personally and was able to add without doing extra research), the median graduation-to-job time was 2 years. (Keep in mind that some people are on here twice, getting a 1- or 2-year gig right away, then a more permanent position later.) Seven people got jobs the same year (SEVEN!) as their PhD, and the duration went all the way up to 20 years (for a senior scholar landing a senior gig). If we limit it to tenure-track assistant professorships (or equivalent, as best as I can tell), here’s the breakdown:

Four candidates (FOUR!) won a job the same year they received their PhDs, and seven more won it a year after receiving their PhDs. The median is still two years.

Now there are many reasons why someone might win a tenure-track assistant professorship seven years after receiving their PhD. They may have had a tenure-track gig for several years, but wanted to move to a better institution, or closer to family, or where there are better professional opportunities for their spouse, etc. However, it is important to note how few of these 28 jobs are won by people graduating that year — just four — and how after four years post-graduation, there are very few people winning tenure-track gigs. The missing data may totally change this profile, of course. But if this is at all representative, those are important things to consider.

What to do?

Again, this is incomplete data, so please don’t base any major life decisions solely on the charts and tables in this post! However, I do strongly encourage anyone pursuing or thinking about pursuing a PhD in music theory — or considering a move to a new job — to get as much of this data as early in the process as possible. I also encourage those who are recruiting and advising graduate students to help them find this information, too. And notice that I left out the theory-and-something-else jobs. There are a large number of those. (Aspiring) theorists who want to brave this market should take time to build cognate skills and forge interdisciplinary collaborations. These will expand the job possibilities within music academia, as well as help you explore other ways to apply your music analysis, writing, and teaching skills in other domains where the jobs may be more plentiful.

Let me emphasize that last point. We tend to think of getting a PhD in a field, but not landing a tenure-track gig in that field, as a failure. Nothing could be further from the truth. There are numerous fiscal and political factors that have led to an increasing number of those scenarios in the past few years. It’s not true that “all good people get jobs” anymore — if it ever was. Not getting a tenure-track gig doesn’t mean you’re not “good people.” Further, a good PhD program should instill skills and modes of thinking that are applicable in a wide range of fields. Finding a job where you make a good living, can choose where you live, and have an appropriate work/life balance is a success, even if the job is outside the field in which you specialized in grad school.

Get as much info as you can. If you have students, share it with them. And then keep your options open. Music theorists are, if anything, people who can think creatively and find patterns behind the mystery. Let’s use those skills to help ourselves, and each other, make a go of this thing called life after graduate school.