This morning, my four-year-old was reading Green Eggs and Ham to me. I’ve heard that Dr. Seuss was intentional about using developmental psychology to inform how he wrote his books to help children learn how to read, and it is amazing to watch that process in action.

There are several things going on, but one that stood out to me today was the pace at which Seuss introduced new words to young readers. Green Eggs and Ham in particular seems to take advantage of the ways the brain forms new long-term memories to help children learn new words effectively.

Research in both cognitive science and in learning theory suggest that the optimal way to form a new, resilient long-term memory is to practice recall just before you are about to forget. If you wait longer, the memory will become inaccessible, and you will have to form it again from scratch. Don’t wait long enough, and you’ll be using short-term memory, not long-term memory, and thus not strengthening the right neural networks.

What does this look like in practice? It looks like introducing a new word with several close repetitions ― using short-term storage as working memory is figuring things out ― and then gradually spacing occurrences of that word further and further apart as the story progresses. This helps the reader move their work from short-term to long-term memory, and accounts for the fact that each time the memory is strengthened it will take longer to (almost) forget.

Since my research and upcoming courses have me thinking a lot about coding, statistical modeling, and cognition, naturally I wondered if I could model this process and analyze a few children’s books. I didn’t create a full-on statistical model, but I did come up with an analytical framework and write a script that would allow me to make some visualizations and compare books. The results were pretty cool.

TL;DR version: Dr. Seuss does write (at least some) books consistent with research on memory formation, books that have a good chance of helping kids learn, and remember, new words. But not every book billed as “learn to read” or “step into reading” do the same.

The model

To analyze how well an author matches the memory-formation strategy described above, I decided to measure two things and look for trends: how many times a word occurs, and how close together. I wanted to note how these things changed over the course of the book. So for each word, I needed to know how long it had been since the previous occurrence, and what proportion that word represented of all the words read so far. Then I could simply plot these values over time and look for patterns.

I decided to leave in stop words ― articles, conjunctions, etc. ― which are typically dropped from text analyses. They tend to be dropped because they pollute the data when looking for meaning. However, because stop words form a high proportion of the words a reader will encounter, and because they are often linguistically older and thus do not follow the “rules” of modern phonics (think the, you, of, etc.), they are important for young readers and thus may be points of focus in a book meant to help a child learn to read. I also did not stem words (treat run, runs, and ran as the same word) since, again, those differences may be the point of focus in learning to read.

The hypothesis

What was I expecting?

I was expecting that a book optimized for learning new words would contain certain key words (learning targets) whose distance between occurrences would increase over the course of the book, and whose proportion of occurrence (relative probability) would rapidly increase through the first few occurrences as the word was joining the repertoire, and then level off and gradually decrease as it spaced out and new words were added to the repertoire.

I was expecting that a book aimed at children, but not at teaching them to read, would contain a similarly small repertoire of words, but would have more random-looking, or at least noisy, data in each of these domains.

I wanted to test Green Eggs and Ham, of course, alongside a lesser-known “learn-to-read” book ― I chose Dragon Egg by Mallory Loehr ― and a children’s book written more for the narrative ― I chose Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit.

The script

My work on The Lieder Project gave me a starting place ― code that already does most of what I wanted to do. So I added some tweaks and functions, and created this script for processing a text file. Visit the script and accompanying data (original books omitted for copyright reasons, except for Potter) if you want to dig in yourself.

The fun stuff

I loaded up the data files my script created in R and created some visualizations to see what patterns I might find.

I began with the running probability of a word’s occurrence given what had been read so far.

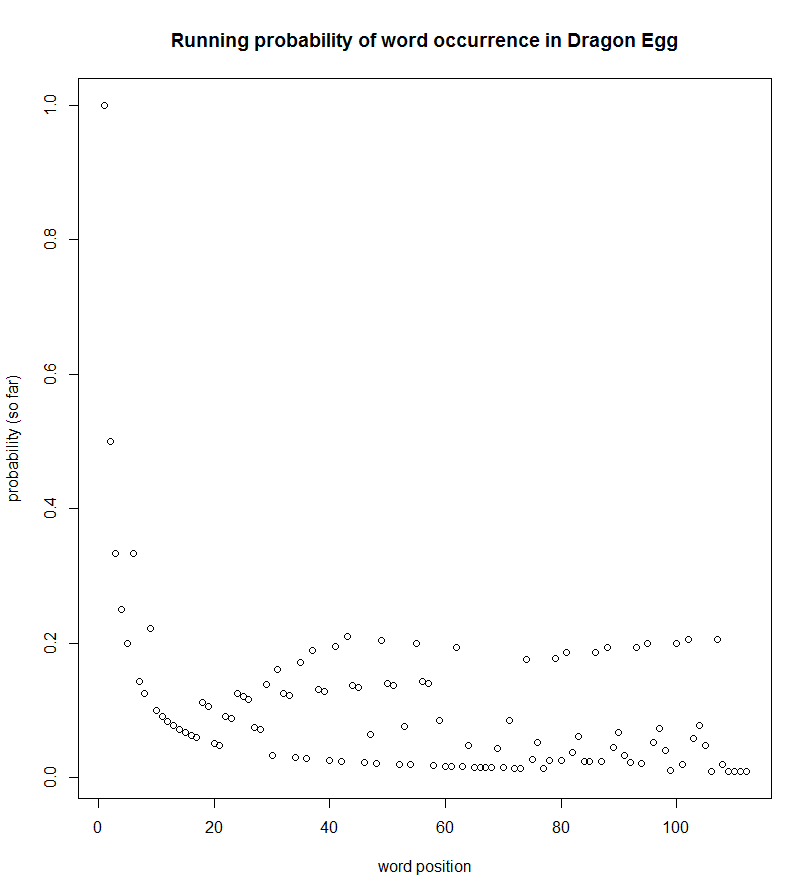

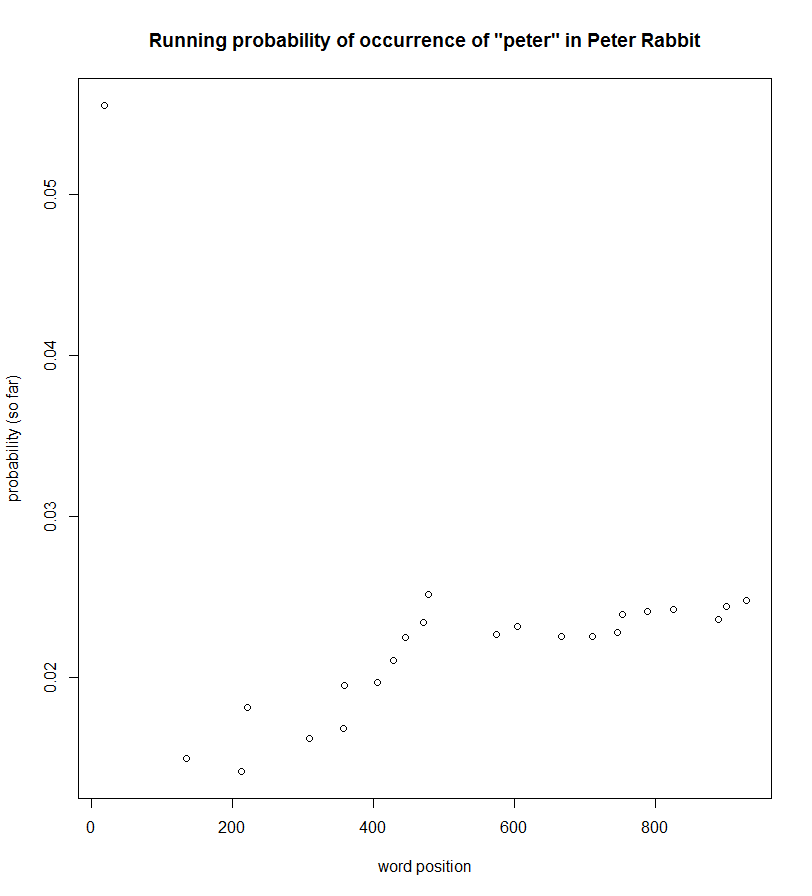

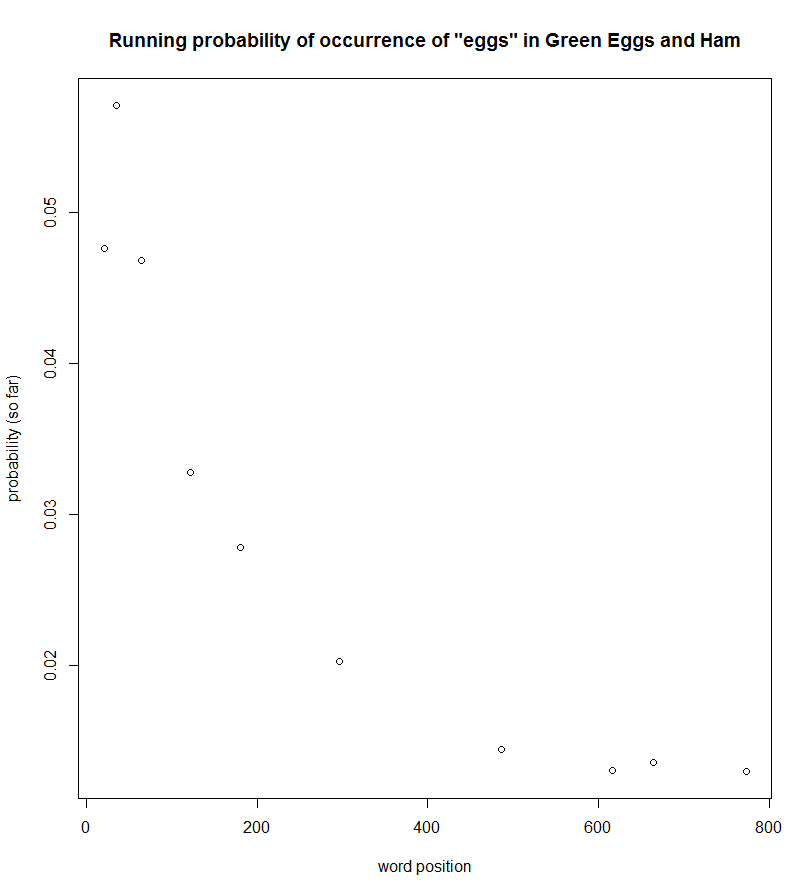

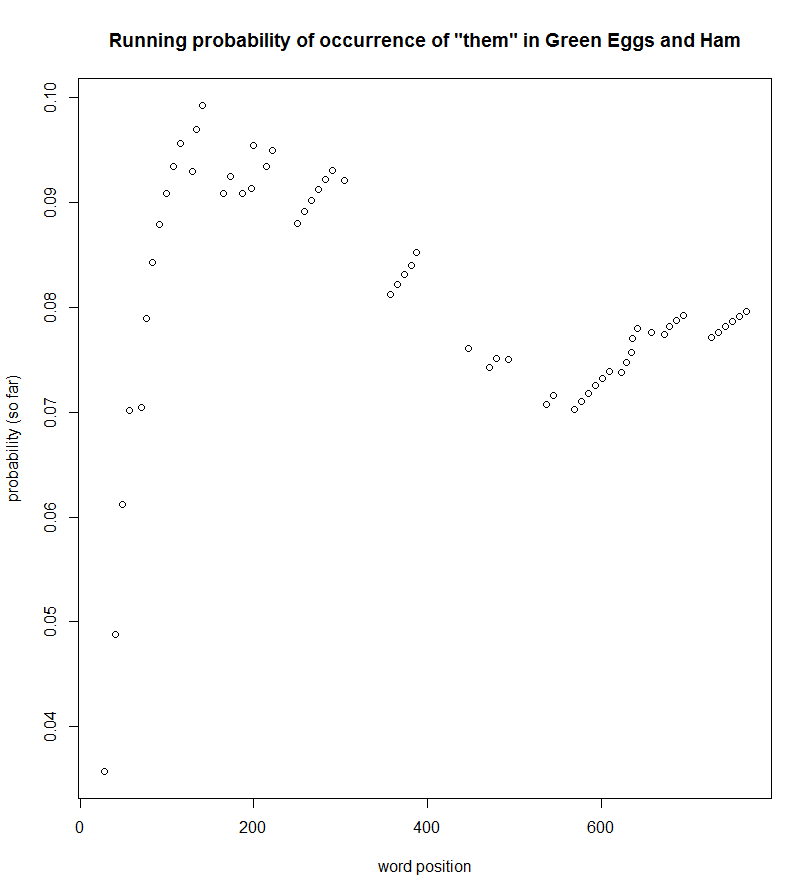

Notice that while each book has a noisy band of low-probability words throughout, both of the learn-to-read books have separate bands of high-probability words that occur regularly. This looks to me like evidence of learning targets ― words receiving emphasis beyond that of “regular words.”

But what are these words?

Here are the most common words in each book:

- Peter Rabbit: the, and, he, to, a (the most common non-stop words were peter, mr, mcgregor)

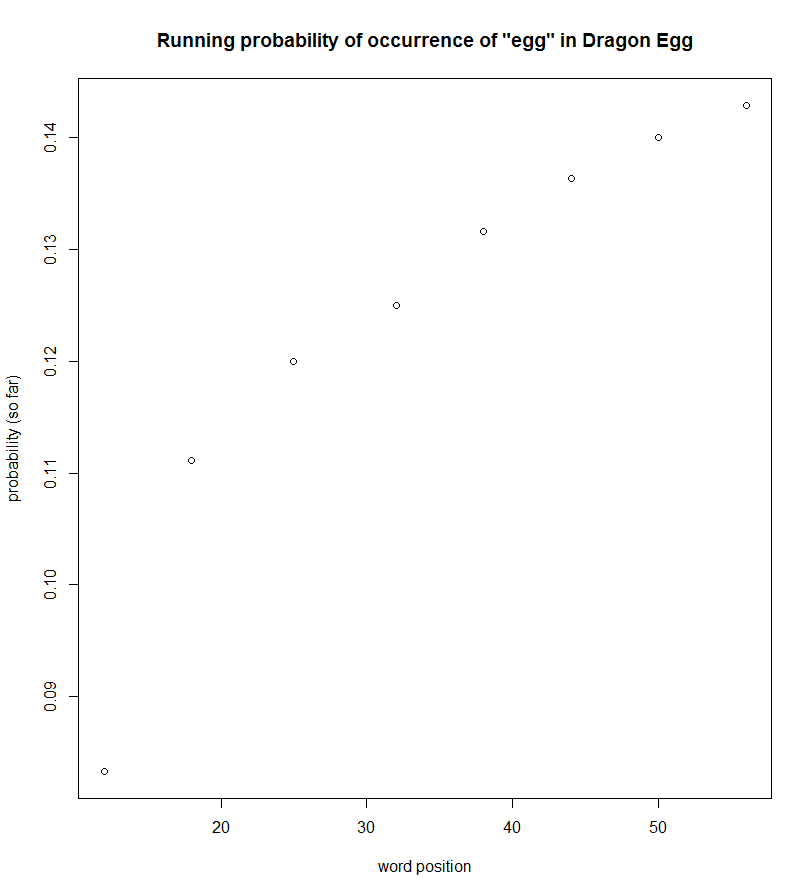

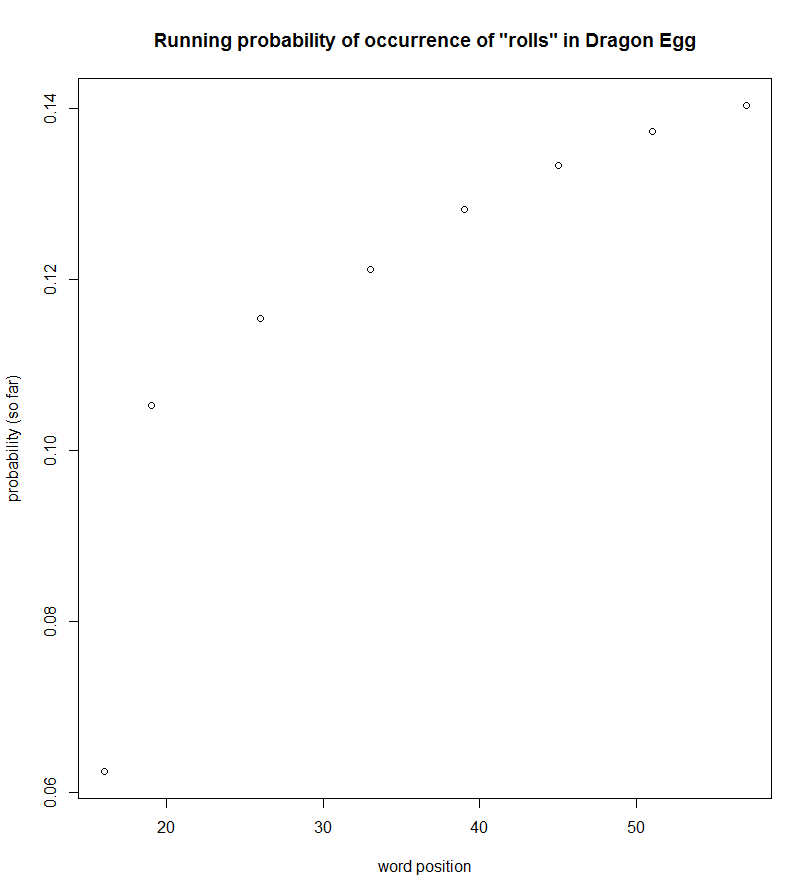

- Dragon Egg: the, rolls, egg, dragon, baby, flies (everything else occurred three times or less)

- Green Eggs: not, i, them, a, like (other high-probability words that are likely learning targets include you, would, eat, could, eggs, train, mouse, house, fox, box)

I plotted the distance-since-previous-occurrence and the running-probability-of-occurrence for a number of these words. Here’s what I found…

First, as a baseline, the distance-since-previous-occurrence plots showed nothing but noise in Peter Rabbit. There was no discernible pattern in terms of how close/far occurrences of words like peter, mcgregor, the, or and were from each other. Most of the probability-so-far plots were likewise noisy. But some showed a pattern opposite to the proposed learning theory. For example, the probability of reading the word peter increases throughout the book.

On the other hand, I found one word that matched the learning theory hypothesis: and.

But I’m fairly certain this is an anomaly. :)

Green Eggs and Ham, on the other hand, showed evidence of several learning targets following the proposed learning theory. Here are a few of them (running probability of occurrence shown ― an initial spike followed by a gradually descending tail matches the learning theory).

Not all words follow this model, but a number of them do, which makes sense if we assume that the book is meant for readers who already know some of them.

Dragon Egg is interesting. It is part of a “step into reading” program from Random House that assigns levels to books based on their difficulty. While that system may help parents and kids identify appropriate books, this one doesn’t seem meant to follow the learning theory we see associated with Seuss. In fact, five of the top six words follow the opposite pattern of that suggested by the learning theory. Here are a couple…

I don’t mean this to be a jab at Loehr by any stretch of the imagination. There are many factors that go into word (density) choices when writing a children’s book. However, the contrast between these three examples ― for me, anyway ― highlight the choices made by Seuss and the potential benefits they have for young readers.

Obviously, these are just three books, so let’s not draw any conclusions here. But knowing what we know about Seuss’s approach, seeing it in action with my kids as they learn to read, and then seeing this data visualized has given me a little more appreciation for these books, and for the wonder that is the brain of a child learning.