Musicianship Resources

Applied chords

Tonicization is the process of momentarily emphasizing a non-tonic chord by using chords borrowed from the key in which that chord is tonic. Unlike modulation, there is no cadence in a new key, only a short progression of chords borrowed from another key.

The chord that is tonicized is typically a chord that belongs to the present key. The chords that emphasize it are usually the chords borrowed from another key. And these chords are usually chromatic alterations of chords native to the present key.

The most straightforward example is when a subdominant chord is chromatically altered by changing fa to fi, and then progresses, like usual, to the dominant chord. This alteration of fa to fi turns a regular subdominant chord into a chord that has a dominant function in the "key of the dominant."

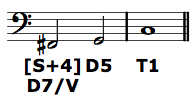

For example, take the chord progression F–G–C in C major. We would analyze this as S4 D5 T1. If we change fa (F) to fi (F#) in the F chord, we get F#dim–G–C. In the key of C, we analyze this progression as [S+4] D5 T1, showing the chromatic alteration by square brackets, and the raised scale-degree four with a plus. However, we can also note that F#-dim is native to G major; it is a dominant-functioning chord (D7) in the key of G—the key in which the following chord is tonic. Thus, we can interpret the [S+4] as a D7/V, read "D seven of five." It is at once a chromatically altered subdominant in C and a dominant in G, and both of those identities reflect its function in this example progression.

Such borrowing of chords can happen for any non-diminished triad in the home key. That is, any diatonic triad can be preceded by a chromatically altered chord that also functions as a dominant chord in which the following chord is tonic. Thus, the example progression of F#dim–G can occur in any key to which G major belongs: G major, C major, D major, B minor, A minor, or E minor.

Two things will always be true of the applied chord, which must be reflected in any functional bass analysis, and which can help you spot errors in your analysis:

- The chromatically altered chord will function as a dominant chord in the key of the chord that follows it.

- The chromatically altered chord will be an alteration of the function that logically precedes the function of the chord that follows it.

On the latter point, if the tonicized chord has tonic function in the current key, the applied chord will be an altered dominant of the current key. If the tonicized chord has dominant function in the current key, the applied chord will be an altered subdominant of the current key. If the tonicized chord has subdominant function in the current key, the applied chord will be an altered tonic of the current key.

Analytical notation

Like chromatically altered subdominant chords, every applied chord will have two elements to its functional bass symbol. First, on the normal line of functional bass analysis will be a symbol showing its function in the current key and the scale degree of the bass note (with "+" or "–" for altered bass pitches), surrounded by square brackets to signify that the chord is chromatically altered. (The square brackets are necessary no matter in which voice the chromatic alteration occurs.) Second, below the normal line of functional bass analysis will be a symbol denoting the key from which it is borrowed and the functional bass symbol the chord would have in that key.

In our above example of F#dim–G–C in the key of C, the regular functional bass line would read [S+4] D5 T1, and below the [S+4] would be the symbol D7/V. The latter symbol uses a slash to denote "in the key of" and a Roman numeral to denote the tonic of that key relative to the current key. We will use Roman numerals similarly when studying modulation to denote tonics of key areas to which the music modulates. Roman numerals, however, are never used to denote chordal roots in the context of a functional bass analysis.

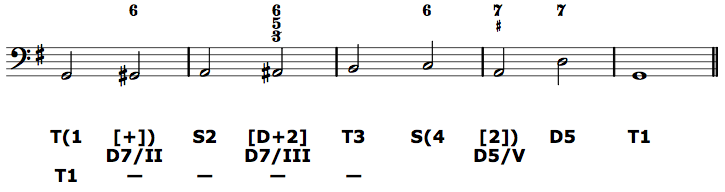

The following figured bass line demonstrates the proper notation for a number of different applied chords in the context of a single key. Note the functional bass symbols for the chromatically altered chords, the use of slash notation and Roman numerals, and the functional relationship of applied chords and the tonicized chords that follow them. Note also that if a scale degree repeats, but in altered form, in the bass, only a plus or minus need be included in the functional bass. Hence T(1 [+]) rather than T(1 [+1]).

Scale degrees in applied chords

Just as the various dominant functioning chords in a key will contain some combination of the dominant-functioning scale degrees—sol, ti (occasionally te), re, fa, and/or le (occasionally la)—each category of applied dominant chords will have their own set of usual scale degrees. They are as follows.

D/II — di, mi, sol, la, and te.

D/lowered-III (minor) — re, fa, le, and te.

D/III (major) — ri, fi, la, ti, and do.

D/IV — mi, sol, te, do, and ra.

D/V — fi, la, do, re, and me.

D/lowered-VI (minor) — sol, te, ra, and me.

D/VI (major) — si, ti, re, mi, and fa.

D/lowered-VII (minor) — la, do, me, and fa.