The following is a talk I shared at Moravian College to humanities faculty as they work through issues of blended learning in a liberal arts context. The original title of the talk was “Digital affordances, digital limitations: blended learning in liberal arts education.” I have since updated it for a presentation at Bates College.

When I was in elementary school, I had a wooden desk with cutout sections at the top. The long skinny sections, I assumed, were pencil holders, and I used them as such. But the square in the corner I didn’t quite understand. My classmates and I used them for erasers, paperclips, and (if I remember correctly) spitballs and other contraband. But none of us really knew what they were for.

It was years later when I realized that not only were the desks leftovers from a previous generation, but so was the design. These square cutouts were for ink wells. In fact, it was only at this time that I learned why we called the study of handwriting penmanship when we were only allowed to use pencils. In those bygone days, not only did they use pens ― fountain pens, dip pens, quill pens ― but they studied the proper use of the pen, not just how to write legibly.

Recently I’ve become something of a fountain pen geek. I say geek rather than connoisseur because I haven’t spent ― and in fact I don’t have ― enough money to consider myself even an armchair expert in fine writing implements. However, I have several inexpensive fountain pens, each with a different nib. And on my standing desk at work, alongside my Microsoft Surface tablet and my 4K display, I have three wells of ink.

Over the past two years, I’ve discovered the enjoyment, and at times the zen, of writing with fountain pens. It’s taught me several things. It’s taught me the value of good paper. Pencils and ball points can write on just about anything, but a fountain pen just doesn’t work right on cheap, scratchy paper. It’s taught me how to write more neatly. Not only do I try a little harder when I have a nice pen and nice paper, but the pen works better when I use proper form. As a left-hander, I’ve always struggled with neat handwriting (and with incompetent or not-so-understanding penmanship teachers), so it feels good to write something by hand and like the way it looks.

Writing with fountain pens has also taught me something about technology. A good pen and a nice notebook are probably my favorite technologies, alongside a variety of musical instruments. But as I’ve used them more and more, and used them alongside pencils, ballpoints, dry erase markers, and various digital devices, I’ve grown keenly aware of the affordances and limitations of each. As a left-handed writer, I am acutely aware of the limitations. Let me illustrate.

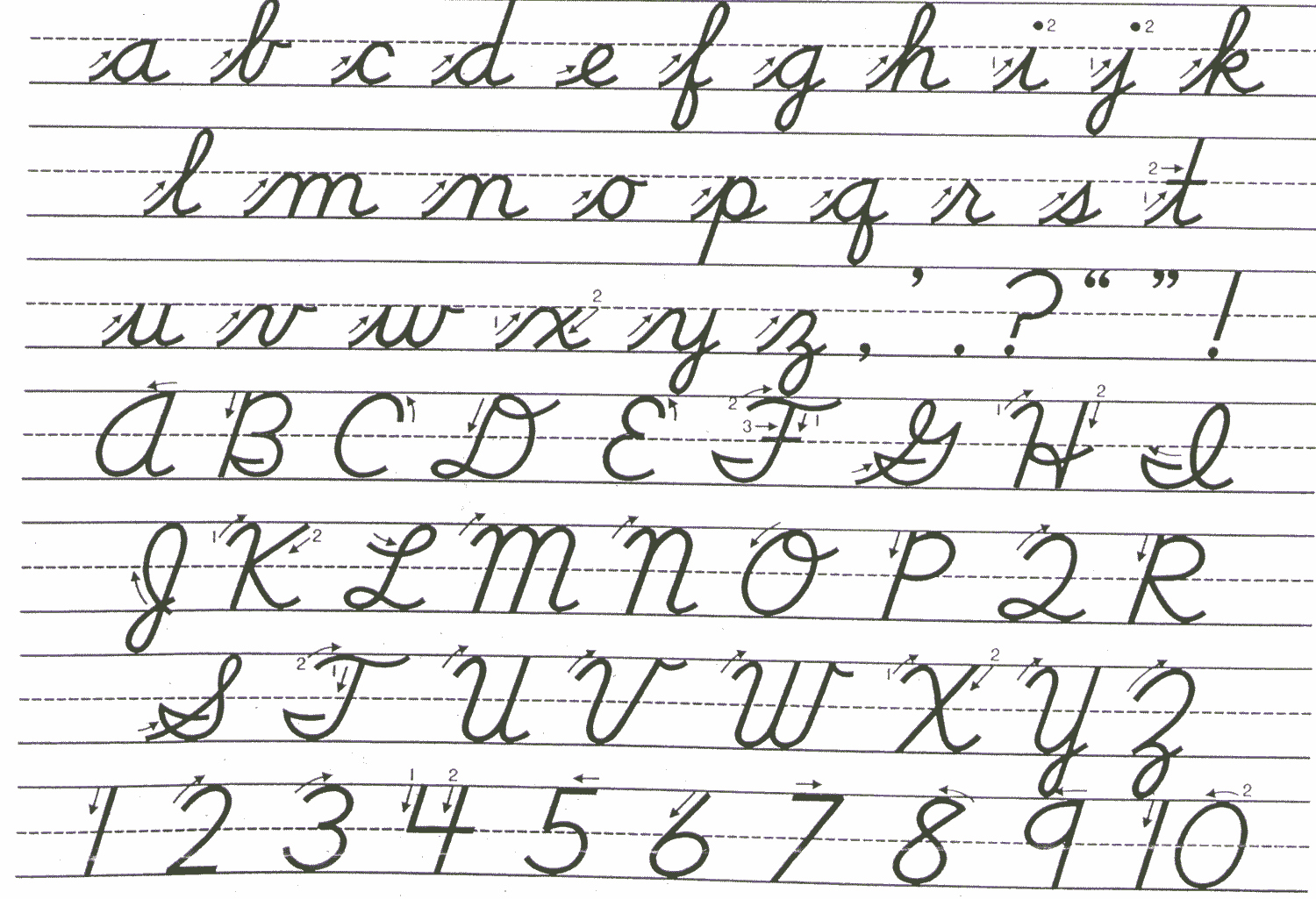

Remember this?

For several years in elementary school, I was required to write every school assignment in cursive. I hated it. For roughly the same several years in elementary school, I was constantly hounded by my teachers for my poor handwriting. I was gifted, and stereotypes about gifted children include rushing through easy schoolwork, leaving a sloppy mess behind, so they can more quickly move onto something of interest. This was probably true of me, and it’s certainly true of my oldest (right-handed) son. But this wasn’t the whole story. My teachers, especially my third grade teacher, were very particular about the direction my pencil moved when making letters. Why must I make my O’s counterclockwise, even when printing?! Why must the “flag” on my 5’s be an additional stroke?

I learned why only last year. I mentioned before that writing with a nice pen on nice paper makes me want to write especially neatly. As a left-handed writer, this is difficult, especially with fountain-pen ink. To make the ink move smoothly through the feed and down the nib, the ink must be wet. If it dries too quickly, it will clog the pen, and the pen will alternate scratches and blobs. But as a left-hander, my hand follows what I write, and if I’m not careful, it smudges the ink.

So I took a page out of Leonardo da Vinci’s book, and I tried mirror writing (where you write right-to-left with reversed letters). It only took me a little while to get the hang of it, and almost instantaneously I was able to write as quickly as left-to-write, and much more neatly. No smudges, prettier letters, more even spacing… Everything just worked. I eventually abandoned mirror writing, though, when I realized that I couldn’t read it nearly as readily as left-to-right letters. But the lesson stuck with me. Being able to see the letters as I write and not worrying about smudging the ink after I write meant a more natural hand position, and better handwriting overall. This is what it’s like to be right-handed!, I thought. And that’s when I realized that the limitations of my own penmanship were directly related to the affordances of pen, paper, and ink for right-handed writers.

I noticed something else, too. Remember those struggles with cursive? As soon as my teachers let me, I abandoned it for printing. For a while, I was only writing in all capital letters. But the fluidity of the fountain pen made me want to try cursive again. It was a mess. The lack of practice, plus all the old problems, made it pretty much a fool’s errand. But then I tried it in mirror writing. The strokes were unfamiliar, so it wasn’t easy, but after just a little practice, like printing, it was better in mirror writing than in left-to-right. Not only was it neater, though. I learned through experience why cursive developed the way it did.

Have you ever wondered why the capital letters all seem to start with a little uptick? (Which, if I’m honest, looks goofy and always struck me as silly.) When I try to write cursive, left-handed, with an italic nib, those upticks are very awkward, and they look strange. I’ll tell you that if I were using a dip pen, or especially a quill pen, I would make a complete mess of the page, as the pen would get stuck, then skip and splatter ink everywhere. This is why many left-handers “hook” their hand when they write, or turn the page sometimes a full 90 degrees. It’s the only way to make it work. (I’ve verified this while attempting calligraphy with a quill. It only works 90 degrees off-axis.) But if I use mirror writing, the motions are the same as a right-handed writer. The uptick actually starts with the pen going down and then sideways. This is an ideal motion to get ink flowing at the start of a word: the downward motion gets the ink started, and the sideways motion gets it moving at a steady, but not too torrential, flow.

If we look back at the chart of cursive letters, we can see that this angle of motion begins many of the letters, both upper- and lower-case. This motion is, for a left-handed writer, awkward at best, prohibitive at worst (especially with a quill). But for a right-handed writer with a quill or dip pen, they are absolutely essential to legible writing.

And that’s the key here. Why did I learn cursive as a young student? Why was it the required mode of written discourse for several (painful) years of my childhood? Because for past generations, it was the mode of writing that best lined up with the affordances and limitations of the dominant writing technologies for the dominant class of writers. Because of that, this medium became not just a form of discourse, but educational content in its own right. And when new writing technologies emerged that were more practical and less expensive, the content of cursive penmanship was preserved until there was competition for that pedagogical space. For at least three generations, content was taught not because of its own intrinsic value, but because of its technological expediency for past generations. New wine in old skins. Or, rather, old wine in new skins. Only now that digital technologies are competing for that space are we discussing the relative merits of teaching cursive to our children in American elementary schools.

To sum up, this story about my struggles with cursive illustrates two pedagogical problems that can easily emerge when choosing a technology to adopt:

- Choosing a technology based on its affordances for members of the dominant class (or simply whatever class the developers belong to) leaves people out.

- If we don’t constantly re-evaluate our educational purposes and our technological choices, we’ll end up wine-wineskin mismatch ― tools and technologies lined up with someone else’s educational goals rather than our own.

Let me illustrate with one more (shorter!) story, one that shows the opposite side of the coin: when old pedagogical practices aren’t up to new challenges.

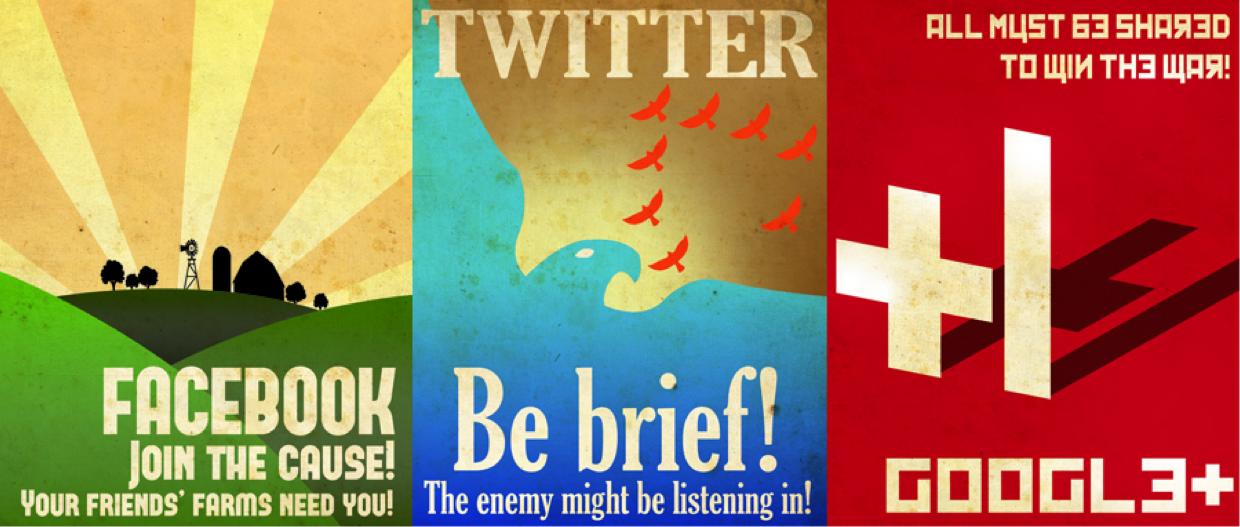

Social media propaganda posters, by Aaron Wood.

Misinformation abounds. This has always been the case, but the problem has become acute in the age of digital communication. As Mike Caulfield and Zeynep Tufekci have been showing in the week following the 2016 US presidential election, Facebook is particularly susceptible to this problem. Of course, Facebook is not alone. The ease with which we can share “news” on social media platforms makes it increasingly easy to contribute to the virality of falsehoods.

I was tweeting about this phenomenon last week. Amid a stream of comments I posted to Twitter about deceptive media practices, I received this two part response from someone I don’t know:

And that does not count the obvious foreign influence of people like Soros.

I’ll throw RT and Putin in there just to keep the balance of the narrative, but the point stands.

This is subtle, and rather artful when I think about it, deception. Let’s unpack it.

The first message is a jab at businessman George Soros, someone the far right often accuses of manipulating leftist activists to suit his own aims. Though it is a common accusation from white nationalists, I hadn’t heard of it before. So I Googled “Soros” to see what the story was. Among results like Wikipedia and Soros’s own web page are white nationalist, fake-news sites talking about reasons that Soros is “dangerous,” a co-conspirator with the Clintons, and the “hidden hand” behind anti-Trump protests. If I wasn’t suspicious of these claims to begin with, these Google results might make me sympathetic with the deception. I’m already distrustful of billionaires trying to influence politics, education, and the media, and one can easily assume that top Google results mixed in with Wikipedia and the New York Review of Books would be fairly legitimate sources. The combination of innocuous and reputable sounding sources on the Google results page (gleaned just from their domain names) and a healthy dose of confirmation bias (he’s a billionaire “activist,” after all!) is dangerous for liberal readers trying to keep up with Twitter’s information bombardment.

The second part of the message is more insidious, though. It makes reference to RT (the state-run Russian news service), Putin, and the “balance of the narrative.” In an attempt to be balanced, the author references two known sources of false information, one of which is admired by Trump and has been potentially (but not definitively) linked to the leaking of information that may have cost Hillary Clinton the presidency. This combines two subtle and effective forms of deception: linking a lie to a truth to make it more credible (we know that RT and Putin are foreign actors that spread falsehood through the media to manipulate people, so why not Soros?), and linking a conspiracy theory (Soros manipulating the left) to an actual conspiracy (Russian involvement in the DNC server hack) to give the conspiracy theory more credulity. This combination of truth with “truthy” lies, aimed at both the propagation of lies and the questioning of what we already know to be true is a psychological abuse tactic called gaslighting. (For more on the impact of repeating “truthy” claims until they are taken for truth, see Audrey Watters’s “Education Technology and the Age of Wishful Thinking.”)

Let me clarify. This isn’t classic gaslighting, which tends to come as a sustained, subtle abuse of one person by another, usually someone in a close relationship with the abused. This is a new brand of digital gaslighting, where large groups of people (and their sock-puppet Twitter accounts and bots) attack both individuals and groups, with the effect of the targeted group losing their collective grip on reality. (This was a common tactic during the GamerGate movement.) Individuals may not question their own sanity, but they question the reality of their friends and allies. They question the truth of things for which there is good evidence, and they become susceptible to truthy lies. And when they uncritically retweet those truthy lies, those truthy untruths circulating alongside sometimes surreal truths fuel the uncertainty people have started to feel about their own movement. Worse yet, they give the attackers evidence to point to about the lies told by the movement, discrediting them in the face of moderates and the undecided. (Several in my social media circles suggested that this was the motivation behind the sharing of a video of Venezuelan protests, captioned as anti-Trump protests in Los Angeles.)

Facing tactics like these, digital literacy and critical thinking about digital media require far more than knowledge of the fallacies of informal logic. Ad hominem attacks, reductio ad absurdum, the intentional fallacy — these pale in comparison to coordinated digital deception, powered by sock-puppet Twitter accounts, SEO expertise, and a Facebook algorithm that privileges fake news. We need a new, critical digital literacy: a deep understanding of the technological, sociological, and psychological implications of connective digital media and how people use it, with a view towards mindful, ethical media creation and consumption. This is more than traditional information literacy applied to digital media, more than technical knowledge of digital media production and network protocols. Connective digital media enables new modes of media creation and human activity, and critical digital literacy requires grokking those new modes, in addition to grasping the implications of porting “traditional” media practices to the digital. And seeing both the good and the bad (and the good responses to the bad) ways in which these new modes are enacted, it is clear that we must engage them, especially those of us who educate. But how do we?

(The previous few paragraphs are excerpted from my article “Truthy Lies and Surreal Truths: A Plea for Critical Literacies” in Hybrid Pedagogy.)

Let’s take a step back, first, and consider the landscape I’ve laid out. After discussing the pedagogy of penmanship, I noted two problems we need to keep in mind:

- Choosing a technology based on its affordances for members of the dominant class (or simply whatever class the developers belong to) leaves people out.

- If we don’t constantly re-evaluate our educational purposes and our technological choices, we’ll end up wine-wineskin mismatch ― tools and technologies lined up with someone else’s educational goals rather than our own.

Crowd-powered deceptive digital media adds more potential pitfalls and a need for new literacies like crap detection, attention management, and collaborative networked knowledge.

In the case of cursive, the new technologies of pencils and ball-point pens caused minimal friction. Very few new skills were required to adopt the new tools, and the old content and methods caused no major conflict with the new tools, so there was no pressure to push cursive out of the curriculum. However, the rise of digital technology, especially the internet, means that not only are computing skills necessary additions to the curriculum, but new modes of critical thinking and creative work ― long hallmarks of liberal-arts education ― are necessary. But surely these new focuses come at a cost? When we add something to our curriculum, to our mission, certainly something has to go? And we certainly don’t want to abandon the things that we have done so well for so long?

This is often the frame around discussions of digital technology and digital pedagogy in higher education, especially in the liberal arts. But I wonder if we can add some nuance to this discussion. If we can move past the idea of courses as containers for content (Slide 12), and zero-sum games of curricular redesign. Can we create a hybrid, or blended, learning environment where we maximize the retention of what we’ve done well for ages while simultaneously taking advantage of new approaches and addressing new needs?

I think some theoretical framework could help us as we address this question. In particular, I’d like to tease out the difference between blended learning, a term you are likely familiar with and which I’ve already hinted at today, and hybrid pedagogy, likely a less familiar concept, but an important one to help us approach the idea of digital pedagogy in a liberal arts context.

Jesse Stommel (my colleague at Mary Washington and co-founder of the journal, Hybrid Pedagogy) writes:

At its most basic level, the term “hybrid,” … refers to learning that happens both in a classroom (or other physical space) and online. In this respect, hybrid does overlap with another concept that is often used synonymously: blended. I would like to make some careful distinctions between these two terms. Blended learning describes a process or practice; hybrid pedagogy is a methodological approach that helps define a series of varied processes and practices. (Blended learning is tactical, whereas hybrid pedagogy is strategic.) When people talk about “blended learning,” they are usually referring to the place where learning happens, a combination of the classroom and online. The word “hybrid” has deeper resonances, suggesting not just that the place of learning is changed but that a hybrid pedagogy fundamentally rethinks our conception of place. (Thanks to @vsuter for helping me work through my thinking on this.) So, hybrid pedagogy does not just describe an easy mixing of on-ground and online learning, but is about bringing the sorts of learning that happen in a physical place and the sorts of learning that happen in a virtual place into a more engaged and dynamic conversation.

…

Hybridity is about the moment of play, in which the two sides of the binaries [teacher/student, analog/digital, passive/experiential, etc.] begin to dance around (and through) one another before landing in some new configuration.

(“Hybridity, Pt. 2: What Is Hybrid Pedagogy?”)

These are helpful distinctions. Let’s start with the idea of blended learning as instrumental, tactical. Isn’t that how we normally hear it described, both from some of our administrators, and especially from legislators and vendors? Blended learning as a technique is often invoked as a way to increase the efficiency, decrease the cost, or up the scale of “delivering” education to students. Framed this way, we assume a lot. We assume that the content of education remains the same; it is the delivery method that changes. We assume that the mark of a good educational method is a high rate of return on investment. And those of us who are (or have been) faculty recognize the familiar marks of a top-down, often unfunded, mandate to “move” our courses into the “digital realm.”

This largely neoliberal and unreflective version of blended learning as an instrumental change is not uncommon. We see it from organizations like Edutopia and Educause, we see it in university teaching resources, we even see it in our president’s policy platform for education. The assumption that education is content delivery leads quickly to the discussion of the best tools for the job, with digital tools often presented as good candidates for information delivery.

But in the liberal arts, we know that education is far more than the delivery of information. As Paulo Freire writes, in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, “The more students work at storing the deposits entrusted to them, the less they develop the critical consciousness which would result from their intervention in the world as transformers of that world” (p. 73). That critical consciousness is at the core of liberal education, not merely informational deposits. It is not, as Eric Mazur quips about lectures, the art of transferring information from the instructor’s notebook to the student’s notebook without passing through the brains of either. Instead, the purpose of education is “the practice of freedom,” a phrase used by Paulo Freire, bell hooks, Richard Schaul, and many others. Or as my institution’s vision states, “We are a place where faculty, students, and staff share in the creation and fearless exploration of knowledge through freedom of inquiry, personal responsibility, and service.” The goal of helping students be active, critical, creative, and engaged in their world, helping them harness their agency to have a transformative impact on the world … these are the hallmarks of liberal education, not information transfer.

That said, digital tools can be used alongside or in place of analog tools to accomplish the purposes of liberal education, as well. In fact, as I illustrated earlier with my experience last week on Twitter, the world we want our students to engage critically, and to ultimately transform for the better, that world is increasingly digital. Blended learning environments can help us help our students have that transformative impact.

But how do we design a blended learning environment for the liberal arts? Were education really just the transfer of information, we would simply present students with information in-person, via a printed book, via an ebook, and via a video lecture, and test their retention on a multiple-choice test to discover the best method for information delivery. The problem is that there is no standardized test for student agency, for transformative impact, for the ability to find new answers we didn’t anticipate, let alone to ask insightful questions that have never been asked before.

That’s where the philosophy of hybrid pedagogy can help. Back to Jesse’s article:

[H]ybrid pedagogy does not just describe an easy mixing of on-ground and online learning, but is about bringing the sorts of learning that happen in a physical place and the sorts of learning that happen in a virtual place into a more engaged and dynamic conversation.

…

Hybridity is about the moment of play, in which the two sides of the binaries [teacher/student, analog/digital, passive/experiential, etc.] begin to dance around (and through) one another before landing in some new configuration.

Let me unpack that a bit more. In The Archaeology of Knowledge, Michel Foucault writes, “We must question those ready-made syntheses, those groupings that we normally accept before any examination, those links whose validity is recognized from the outset.” He is writing in the context of an exploration of history, in which the task of the modern historian is to disrupt the unities of discourse, unpack traditions that are assumed but on closer examination reveal themselves to be both fraught and ideologically grounded. Writing about written documents, he says:

The book is not simply the object that one holds in one’s hands; and it cannot remain within the little parallelepiped that contains it: its unity is variable and relative. As soon as one questions that unity, it loses its self-evidence; it indicates itself, constructs itself, only on the basis of a complex field of discourse (p. 23).

I’m convinced that we can say the same about the “unities of [pedagogical] discourse” as well. The motto of the journal Hybrid Pedagogy is that “all learning is necessarily hybrid.” Putting that motto in dialog with Foucault, we can say, “all elements of education are necessarily hybrid.” They are variable and relative, fraught and fragile. And as soon as we question their coherence, they lose their self-evidence. But just like Foucault’s historical objects, when we question their unity, they don’t just fall apart. They reveal their variability, their relativity, their hybridity “on the basis of a complex field of discourse.” And with knowledge of that field, and critical reflection on where the field is going, where it could be going, we can reconstruct new unities ― themselves hybrids as well ― as we (re)design learning objects and environments.

Take the course as an example. In the course, there are typically two roles: teacher and student. (We’ll leave aside TAs, graders, and tutors for the sake of illustration.) What is a teacher? We could define it in a number of ways ― the person with expertise relative to the course content, the person who communicates that expertise to others, the person who designs the course, the person who assesses the progress of others in the course, etc. Likewise we could define a student as the person lacking in (and seeking) expertise in a subject, the person who listens with a view toward understanding, the person who submits to course design decisions, the person whose progress is assessed, etc. Are these coherent, self-evident unities? Or are they hybrid entities?

Start with the teacher. Instead of thinking about the role of teacher, let’s think about our experience as people in the courses we teach. Do we enter the class with expertise about the subject matter, or with a desire to learn more? Do we come to talk or to listen? What about our students ― or ourselves when we were students? Did we enter the class as students lacking in expertise, or did we have insights to offer? Did we come to talk or to listen? Did we feel like we were usurping the teacher’s role when we spoke? When we ask these questions, it becomes clear that these roles are necessarily hybrid at their core. The critical pedagogy of Paulo Freire asks us to deconstruct the student/teacher binary, but hybrid pedagogy recognizes that that binary never really existed. Student and teacher were always hybrid roles.

With that understanding, new questions open up. If the teacher is not the absolute bearer of expertise, should the teacher be the absolute designer of the course? the one person charged with assessing the progress of others? Or could we build on the hybridity inherent in the roles of student and teacher, and the expertise and agency already possessed by the students, to involve students in course design decisions, in assessment of themselves, each other, the teacher? These are the questions of hybrid pedagogy.

Now let’s bring them to the concept of blended learning. As a purely instrumental concept, blended learning assumes the self-evident, intrinsic unity of concepts like digital and analog, online and in-person. But let’s ask what these things mean. Let’s start with online. What is “purely” online learning? [in-person discussion] What is “purely” in-person learning? [in-person discussion]

These concepts are already hybrid. Online students rarely do all of their learning in front of a screen. And even students in a homework-free class cannot contain the cognitive and bodily work of that class entirely within the boundaries of the class. They think about it when they leave, they talk about it with others, it changes how they interact with the world, maybe even keeps them awake at night. So if they are already hybrid by nature, what does it mean to blend them? And what does it mean to hybridize online and in-person, digital and analog in the context of an already hybridized understanding of teacher and student? (I’ll ask this rhetorically for now. We can cycle back to this question at the end of our time together.)

Let me share a couple examples of what this might look like.

After hearing Cathy Davidson’s keynote at Digital Pedagogy Lab’s 2016 Institute this summer, in which she discussed co-creating a course syllabus with her students, I was inspired to do the same for my Digital Storytelling course in the fall. I knew it would be difficult to co-create the entire syllabus with my students, since it was my first time teaching the course, since I was teaching it alongside two other sections and in line with a well known tradition, and since it was fully online with many students who had never taken an online course before. So I decided to create a general framework for the course syllabus, and then undertake what I called the “Syllabus Sprint” during the first week of class. Here’s how I presented it to my students:

Welcome to Digital Storytelling/DS106! This is your course. So while there are elements to the course that will be required in order to be consistent with the course description and general institutional requirements, a large part of the content, assignments, and assessment scheme will be determined collaboratively as a whole class. So this week, we’ll largely be focused on a Syllabus Sprint ― working together to fill in the gaps in the course syllabus to line up with the goals and interests that you bring to the course.

Following are assignments for the first week that will help us get through that process. Nothing is due until Friday, September 2, but if you want to have any significant impact on the direction the course will take, you’ll want to dive in right away and contribute to the discussion from the beginning.

I assigned readings that would help them thing about things like online community, assessment, self-assessment, and Domain of One’s Own, the platform that much of their work would be published on. Then I gave them this assignment:

Syllabus Sprint

Simplicity is about subtracting the obvious and adding the meaningful. -John Maeda

The following elements of the course are up for a collaborative decision this week:

Course theme. Take a look at what the syllabus says about the course theme. Then go to the #coursetheme channel on Slack to offer your ideas and respond to others.

Assignment types. Some assignment types are already determined and listed in the syllabus. Are there others that you would like to engage in? What kind of projects do you want to do? This will, of course, be determined in part by the course theme that we choose, and both the theme and the specific assignments will be determined by what you want to get out of the course. The syllabus links to some places to look for inspiration. Add your thoughts on this in the #assignments channel on Slack.

Workload. Under “Assignments and types” on the syllabus, a portion (albeit a significant one) of the traditional DS106 workload is listed. How much work should be added? How often should we do Daily Create assignments? What balance of reading/annotating/creating/writing is appropriate and in line with your goals for the course? How flexible should deadlines be? Add your thoughts on this in the #assignments channel on Slack.

Assessment schema. How will work be assessed? By whom? What will it be worth? How will grade information be communicated? I have a lot of thoughts about this, but I want to hear what you think will be best. Then I’ll share my ideas, and we’ll (hopefully) come to a consensus. Add your thoughts on this in the #assessment channel on Slack.

Anything else? What is missing? What are you uncomfortable with? Share any other ideas or thoughts you have about the syllabus and the course plan on the #miscsyllabus channel on Slack.

These ideas should all be provided and discussed on Slack by Friday afternoon, September 2. I’ll mull things over on the weekend, especially if there are areas where we haven’t reached complete consensus, make final decisions based on our discussions, and post the results to the syllabus on Monday, September 5.

In the end, we settled on a course theme, assessment schema, and assignment schedule that I wouldn’t have come up with myself. In my opinion, the collaborative results were better than I could have come up with on my own. There is a healthy balance of different student interests in the course theme we came up with, there is a healthy balance of instructor guidance and student self-assessment in the grading system we settled on, and students were more open to request changes to the assignment schedule once things got underway, at least in part due to the ownership they felt about the syllabus they helped create.

Another example comes from my in-person course in Computational Music Analysis, a cross-listed course for music and computer science majors at the upper-division and master’s level. The first third of the course was content-oriented, with the content decisions primarily decided by me. However, after that, the course shifted to a project-oriented setup. As my syllabus states:

Before the mid-point of the course, students and instructor will negotiate a collaborative research project that builds on existing work in the field of computational musicology, is sensitive to the methodological concerns raised in reference to the digital humanities in general, will provide students an opportunity to engage with the public, and will afford students sufficient opportunity to meet the individual course objectives.

This required a flexible assessment system that still gave the students some foothold so they had an idea of where their final grade would end up as they worked on their project:

Because the course is vertically integrated and interdisciplinary, assessment of student work will use contract grading, tailored to individual students’ levels (undergraduate or graduate) and disciplines.

…

All students will propose a course contract soon after the collaborative research project has been decided. (Model contracts are in the class shared folder on Google Drive.) This contract will articulate the grade desired and layout a work plan that is appropriate for their interests, field, level (grad/undergrad), and desired grade. Once approved by the instructor, these contracts will bind students to the work laid out. However, amendments to the contracts, if necessary, can be requested in writing well in advance of the relevant course deadlines. Students who fail to meet the requirements of their contract will receive a C if core requirements are met, or a D or F, if core requirements are not met. Students who meet the requirements of their contract will receive the grade listed on the contract.

This was the most fun I’ve ever had in a class, and I’ve done it twice. It also received the highest student course evaluation ratings of all my courses. And the work the students produced was high-quality. In fact, several of them collaborated with me on a follow-up project, and we recently submitted an article to a scholarly journal as co-authors. (Oh, and everyone got an A.)

There are smaller, simpler ways to start, if you’re reticent to hand the reigns over to your students in regard to major course decisions. For example, hybridize the textbook by assigning Wikipedia … and having the students find errors or gaps in those Wikipedia articles and submit corrections to Wikipedia. Hybridize your lecture by “flipping” the class for a unit: make instructional readings and/or videos available online, and turn the in-class portion of your lecture class into a seminar or lab course for a day or two. Or simply replace essays written only for the instructor and presentations only meant for the class with digital projects that live on the web and are meant for a public audience. Not only is that a great opportunity for students to engage the public with their work, but the next time around, students can build on the work of the previous class, adding to an ever-growing resource that becomes more useful to the world with each course offering. I’ve done all of these things myself, as have many of my colleagues at Mary Washington. I’d be happy to discuss specific ideas in more detail later, for those who are interested.

During graduate school, I took an course on musical hybridity with ethnomusicologist Sarah Weiss. In an article she wrote following that course, she concluded:

Hybridity is only a problem if one essentializes boundaries. But boundary fetishism, as Jan Pieterse calls it (2001:238-39), is something that humans seem to crave. Boundaries define what is inside through negative comparison with that which falls outside. But over time boundaries shift and seep, burst and reform with new contours, new exclusions and inclusions. If millions of lives have been lost in twentieth-century wars over boundaries ― cultural and geographic ― billions more have been enhanced and created over human time through historical mergings and exchanges. Thinking about hybridity and how we perceive it is important because it makes us think about boundaries, be they cultural or genre. It makes us question our expectations for and ideas about the nature of boundaries, in particular, what they mean both to us and to others. Mapping critical responses to hybridizations in whatever form they take tells us a lot about our own perspectives and those of others on those boundaries.

(“Permeable Boundaries: Hybridity, Music, and the Reception of Robert Wilson’s ‘I La Galigo,’” Ethnomusicology 52/2 (2008), p. 233.)

This statement sums up my view of hybrid pedagogy to a tee. Hybridizing our pedagogy ― whether digital and analog, student and teacher, passive and experiential, institutional and independent, as long as it is done carefully and critically ― has the potential to enhance and enrich lives. And critical reflection on hybridity ― including both the intentional hybridization of pedagogical practices and the inherent hybridity of received pedagogical objects ― helps us think about the boundaries we have set around education, and question our expectations for and ideas about those boundaries. Enriching lives and better understanding the world we live in from a diversity of perspectives, that’s liberal education at its best.

So let’s move beyond the instrumental discussion of using blended learning to bring scale up and bring cost down. Let’s not get stuck in a ballpoint pen moment, where we use a new tool to teach old content without reflecting on the what and the why. Instead, let’s take the opportunity to reflect deeply on the fraught and fragile nature of the educational traditions we have received and the novelties we are encountering, and lets work together to transform the world and empower our students to do the same.

All images used in this talk, unless otherwise stated, are in the public domain.