This is part of a series of posts in which I blog through my process of learning API programming in general and the Medium API in particular. For the beginning of this series, see Part 1.

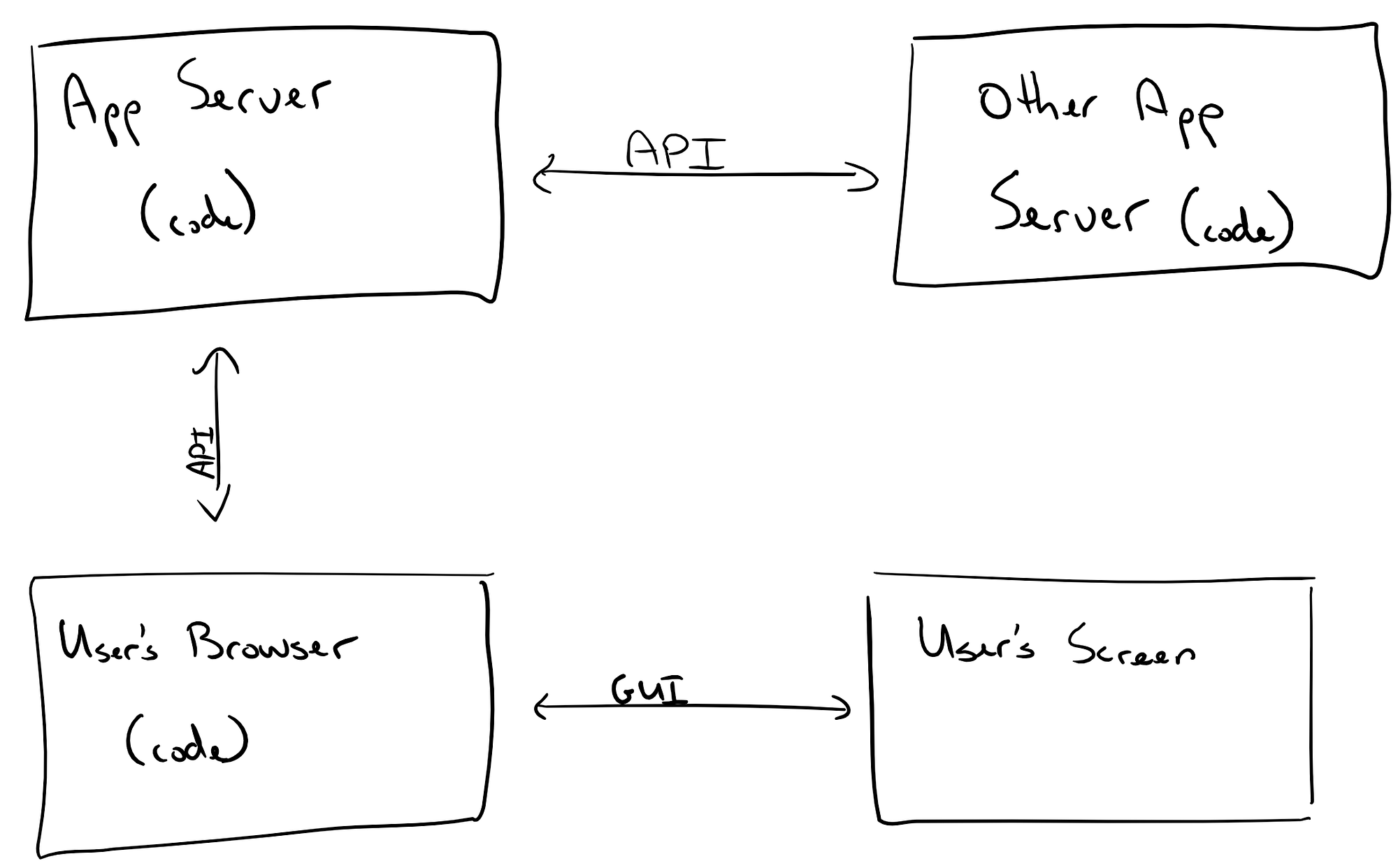

As I explained in Part 1, an API (Application Programming Interface) is the means by which apps talk to each other. If a human interacts with data on a server via a GUI (Graphical User Interface), an app interacts with data on (usually another server) via an API.

So why APIs? Why are they becoming so common? And why are they such valuable tools for (up-and-coming) developers?

Why are APIs becoming so common?

I’m not a seasoned web developer. I’ve been coding in some capacity for a number of years, but I’m pretty new to web apps. However, I’ve been researching them a lot, particularly since starting my new job (which involves a lot of web development), and several themes keep popping up.

First, people are increasingly working on the web rather than on their desktop. And the more people work on the internet, the more their computers (or, at least, their browsers) need to talk to other computers and servers. That means APIs.

Second, the internet is a network of connections. This, of course, applies to people. But the more apps live on the web, the more likely they are to be networked to other apps. Networked apps means APIs. And since APIs facilitate both the connections between a user’s computer and an app’s server, and the connections between two apps’ servers, these two kinds of connections reinforce each other. That is, once an app has an API for connecting to browser-based code, only small modifications are necessary to connect that app to another app on another server. And those API-based connections can make the integration seemingly seamless for the user.

Though APIs connect multiple code bases in the background, a user will only interact via a single graphical user interface (GUI). Good user interface/experience (UI/UX) design will mask that complexity from the user.

Third, API-based apps scale well. I worked with the folks at Trinket a couple years ago to develop a browser-based music notation app that we could integrate into a web-based music textbook. One thing I learned working with them is that if you make the server do all the hard work, adding users means adding (i.e., buying) more servers. Or, it means the app slows down, and you lose those users even before you can buy the servers. On the other hand, if you (like Trinket) let the browser do the computation, while the server gives it the data and the code to run, the server has less to do, and you can handle a lot more users on the same server(s). It also makes the app work faster for the user, since it’s not continuously waiting for data to be sent back-and-forth between the browser and the server. That’s a win-win. And so more and more startups are writing API-based apps, to keep costs down and user experience positive as they seek to grow their company. Of course, the same advantages make it a good option for indie projects.

Finally, in the age of mobile, APIs make it easier to build cross-platform apps. We live in a time of myriad operating system, browser, and interface options. Think about developing a new app that you want to get into as many hands as possible. You have to write an iOS version, an Android version, a Windows Mobile version (though few do), a Windows desktop version, a Mac desktop version… oh, and if you skimp on the desktop versions by running it in a browser, the different (and sometimes outdated) browsers people use still aren’t processing the same code the same way. And then there’s backwards-compatibility issues…

The big problem here is that just about every one of those operating systems expects a different programming language, especially if you want to make use of their latest unique features. That’s a lot of work!

But, if you run the core of your app on a server and offer an API, you can write one main code base and then write simple apps for each platform that connect the particulars of the user interface with the API. You still build multiple mobile and desktop/browser versions, but those versions are much smaller, and when you fix a bug or add a feature to your core, you only have to do it once on your server. (And every user will have the latest update of the core, even if they don’t update their app!)

In my mind, this is just a different flavor of the scaling problem. Instead of scaling to more users, an app may need to scale to a lot of interfaces. An API helps that.

Why should developers master APIs?

If you work for, or want to work for, a company that builds with APIs, then of course you need to master APIs. That much is obvious.

But because of their scalability and compatibility, APIs are also great for indie developers, hobbyists, or people like me who are building apps more-or-less on your own, and with limited server resources. You can do a lot with a little, do the core work in the language you know best (rather than whatever Apple wants you to use this month), and you can avoid rolling out the same fix/feature multiple times on multiple platforms.

Perhaps even more exciting, though, is the ability to build on others’ work, and to let others build on our own work. As hackers, “We are unapologetic tinkerers who neither invent the wheel, nor are satisfied with the wheels already at our disposal.” In the history of free open-source software, that has typically meant that we share code with each other, study each other’s code, and copy/edit/remix it for new purposes. APIs help us extend that. Through public APIs, we can connect our projects to existing projects, not by taking their code, but by connecting our code to theirs. APIs help us connect projects and build something bigger than either project would be on their own.

That’s the what and the why. But how?

That begins in Part 3.

Header image by Heather (CC BY).